Version control

A Version Control System (VCS) is a software system designed to track changes to source code over time. This allows you to carefully track what changes have been made, merge changes from diferent people on a software team, and make sure that only desired changes make it to production.

Common VCS systems include Mercurial (hg), Subversion (SVN), and Perforce. We’ll be using Git, a very popular VCS, in this course. A VCS provides some significant benefits:

History A VCS provides a long-term history of every file. This includes tracking when files were added, or deleted, and every modification that has been made. Did you break something? You can always unwind back to the “last good” change that was saved, or ever compare your current code with the previously working version to identify an issue.

Versioning Software evolves over time, and we often have multiple relevant versions of code e.g., multiple releases that we have provided to customers. Versioning refers to our ability to track sets of changes over time, and assign them semantically meaningful labels or version numbers.

Collaboration

A VCS provides the necessary capabilities for multiple people to work on the same code simultaneously. Changes need to be isolated while features are being developed, and then merged together carefully. We’ll discuss the use of branches, a Git feature, to support this.

Distributed Early VCS systems required near-constant coordination between your working environment and a remote server that hosted the code. Git is different; it was designed as a distributed VCS. This means that you can work on changes to source code without any need to access a central server. Decoupling local and remote changes was one of the major drivers to Git’s early success.

Installation

Git can be installed from the Git home page or through a package manager (e.g. Homebrew on Mac). Although there are graphical clients that you can install, Git is primarily a command-line tool.

Once installed, you will want to make sure that the git executable (git or git.exe) is in your path. You can check this by typing git --version on the command-line.

$ git --version

git version 2.39.3 (Apple Git-146)

Concepts

Version control is designed around the concept of a changeset: a grouping of files that together represent a change to the software that you’re tracking (e.g. a feature that you’ve implemented may impact multiple source files).

Git is designed around these core concepts:

Repository The location of your source code. This can be local (where you are only storing source code on your own machine) or a remote server (e.g., GitHub, where source code is stored in a central location). Git operates perfectly well in either of theses situations. A remote server adds some additional functionality: the ability to perform backups and other maintainance, and more importantly, it simplifies sharing your repository with other people.

Anything you work on with a group of people should be stored in a remote repository like GitLab or GitHub. However, you might have small projects that you never intend to share, and you can also use Git to track changes locally.

Working Directory A copy of the repository, on your local system, where you will make your changes before saving them in the repository. Your working directory contains all of the source code; this is required so that you can build, run your code locally.

Staging Area A collection of changes that you wish to track in Git as a changeset. This should be a set of related changed, reflecting a single feature, bug fix or other logical grouping.

Git works by operating on a set of files (aka changeset): we git add files in the working directory to add them to the change set; we git commit to save the changeset to the local repository. We use git push and git pull to keep the local and remote repositories synchronized.

Git basics

Standard Git functionality is accessed through the command-line. You can use a graphical client, but you will need to understand the command-line concepts to work with Git effectively.

Git commands

Git commands are of the form git <command>. Use git help to get a full list of commands.

$ git --help

usage: git [-v | --version] [-h | --help] [-C <path>] [-c <name>=<value>]

[--exec-path[=<path>]] [--html-path] [--man-path] [--info-path]

[-p | --paginate | -P | --no-pager] [--no-replace-objects] [--bare]

[--git-dir=<path>] [--work-tree=<path>] [--namespace=<name>]

[--super-prefix=<path>] [--config-env=<name>=<envvar>]

<command> [<args>]

These are common Git commands used in various situations:

start a working area (see also: git help tutorial)

clone Clone a repository into a new directory

init Create an empty Git repository or reinitialize an existing one

work on the current change (see also: git help everyday)

add Add file contents to the index

mv Move or rename a file, a directory, or a symlink

restore Restore working tree files

rm Remove files from the working tree and from the index

examine the history and state (see also: git help revisions)

bisect Use binary search to find the commit that introduced a bug

diff Show changes between commits, commit and working tree, etc

grep Print lines matching a pattern

log Show commit logs

show Show various types of objects

status Show the working tree status

grow, mark and tweak your common history

branch List, create, or delete branches

commit Record changes to the repository

merge Join two or more development histories together

rebase Reapply commits on top of another base tip

reset Reset current HEAD to the specified state

switch Switch branches

tag Create, list, delete or verify a tag object signed with GPG

collaborate (see also: git help workflows)

fetch Download objects and refs from another repository

pull Fetch from and integrate with another repository or a local branch

push Update remote refs along with associated objects

You can also type git help on each sub-command to get detailed assistance.

$ git help commit

GIT-COMMIT(1) Git Manual GIT-COMMIT(1)

NAME

git-commit - Record changes to the repository

SYNOPSIS

git commit [-a | --interactive | --patch] [-s] [-v] [-u<mode>] [--amend]

[--dry-run] [(-c | -C | --squash) <commit> | --fixup [(amend|reword):]<commit>)]

[-F <file> | -m <msg>] [--reset-author] [--allow-empty]

[--allow-empty-message] [--no-verify] [-e] [--author=<author>]

[--date=<date>] [--cleanup=<mode>] [--[no-]status]

[-i | -o] [--pathspec-from-file=<file> [--pathspec-file-nul]]

[(--trailer <token>[(=|:)<value>])...] [-S[<keyid>]]

[--] [<pathspec>...]

Setup a local repository

To create a local repository that will not need to be shared:

- Create a repository. Create a directory, and then use the

git initcommand to initialize it. This will create a hidden.gitdirectory (where Git stores information about the repository).

$ mkdir repo

$ cd repo

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in ./repo/.git/

$ ls -a

. .. .git

- Make any changes that you want to your repository. You can add or remove files, or make change to existing files.

$ vim file1.txt

ls -a

. .. .git file1.txt

- Stage the changes that you want to keep. Use the

git addcommand to indicate which files or changes you wish to keep. This adds them to the “staging area”.git statuswill show you what changes you have pending.

$ git add file1.txt

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: file1.txt

- Commit your staging area.

git commitassigns a version number to these changes, and stores them in your local repository as a single changeset. The-margument lets you specify a commit message. If you don’t provide one here, your editor will open so that you can type in a commit message. Commit messages are mandatory, and should describe the purpose of this change.

$ git commit -m "Added a new file"

Setup a remote repository

A remote workflow is almost the same, except that you start by making a local copy of a repository from a remote system.

- Clone a remote repository. This creates a new local repository which is a copy of a remote repository. It also establishes a link between them so that you can manually push new changes to the remote repo, or pull new changes that someone else has placed there.

# create a copy of the CS 346 public repository

$ git clone https://git.uwaterloo.ca/j2avery/cs346.git ./cs346

Making changes and saving/committing them is the same as the local workflow (above).

- Push to a remote repository to save any local changes to the remote system.

$ git push

- Pull from remote repository to get a copy of any changes that someone else may have saved remotely since you last checked.

$ git pull

- Status will show you the status of your repository; log will show you a history of changes.

# status when local and remote repositories are in sync

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/master'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

# condensed history of a sample repository

$ git log --oneline

b750c10 (HEAD -> master, origin/master, origin/HEAD) Update readme.md

fcc065c Deleted unused jar file

d12a838 Added readme

5106558 Added gitignore

Suggestions for using Git

- Work iteratively. Learn to solve a problem in small steps: define the interface, write tests against that interface, and get the smallest functionality tested and working.

- Commit often! Once you have something work (even partly working) commit it! This gives you the freedom to experiment and always revert back to a known-good version.

- Branch as needed. Think of a branch as an efficient way to go down an alternate path with your code. Need to make a major change and not sure how it will work out? Branch and work on it without impacting your main branch.

Tags

A tag is a label that you can apply to a particular point in a repositories history. They are useful to track specific important points in time e.g., a software-release point.

Git supports lightweight and annotated tags:

- A

lightweight tagis just a pointer to a specific commit. Annotated tagsare stored as full objects. They’re checksummed; contain the tagger name, email, and date and have a tagging message.

Useful commands:

git tagto display the tags that have been applied.git tag -a Xto add annotated tag X to the current branch/head.git checkout Xto checkout a branch based on a tag. This is useful with a versioned commit history!

See Git basics tagging for more information.

Branching

The biggest challenge when working with multiple people on the same code is that you all may want to make changes to the code at the same time. Git is designed to simplify this process.

Git uses branches to isolate changes from one another. You think of your source code as a tree, with one main trunk. By default, everyone in git is working from the “trunk”, typically named master or main (you can see this when we used git status above).

A branch is a fork in the tree, where we “split off” work and diverge from one of the commits (typically from a point where everything is working as expected)! Once we have our feature implemented and tested, we can merge our changes back into the main branch.

Notice that there is nothing preventing multiple users from doing this. Because we only merge changes back into main, when they’re tested, the trunk should be relatively stable code.

We have a lot of branching commands:

$ git status // see the current branch

On branch master

$ git branch test // create a branch named test

Created branch test

$ git checkout test // switch to it

Switched to a new branch 'test'

$ git checkout master //switch back to master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git branch -d test // delete branch

Deleted branch test (was 09e1947).

When you branch, you inherit changes from your starting branch. Any change that you make on that branch are isolated until you choose to merge them.

See Basic Branching and Merging and Branching Worklows for more information.

Advanced Git

Commit guidelines

-

Include just what you need in a commit.

Make sure that you are only including related changes, for a single issue. You should aim to have a single commit for every significant feature or bug fix.

If you have multiple, unrelated changes to a file, you can choose which changes to include:

git add -p <file>will prompt you (y,n) for each change to include. -

Write a detailed commit message. You should include:

- Title: The first line of the commit. This should be a concise summary.

- Body: Leave a blank line after the title, and then a block of test. You should include more details, including reasons for the change or other information that will be useful. You should also include an issue number if the commit is related to an issue in GitLab (which it should be).

Branching strategies

Option 1: Mainline development

This is a strategy where the most up-to-date changes are kept on main.

- Relatively few branches from main; only created as needed.

- Merge and integrate features to

mainas they are completed. - Requires diligent testing and care!

- Releases done from

mainbranch.

Option 2: Release and feature branches

More complex strategies will use separate branches for individual work. Merges are done back to an intermediate release branch, where releases are staged and performed. Main is where all release branches are ultimately integrated.

- Multiple branches, at different levels.

- Merge back to

releasebranches as needed. - Provides the ability to have multiple, independent releases.

- More resilient to changes, at the cost of complexity.

This model also illustrates the idea of short-lived vs. long-lived branches. Feature branches are created as needed, but are relatively short-lived: once the feature is integrated/merged back into the long-lived release branch, the feature branch can be deleted.

Feature branches

We’ll standardize on a simpler model, closer to Option 1, where we create feature branches for individual work and integrate changes back to main.

Use this workflow for adding a feature:

- Create a feature branch for that feature.

- Make changes on that branch only. Test everything.

- Code review it with the team.

- Switch back to

mainandgit mergefrom your feature branch to the master branch. If there are no conflicts with other change on themainbranch, your changes will be automatically merged by git. If your changes conflict (e.g. multiple people changed the same file) then git may ask you to manually merge them.

$ git checkout -b test // create branch

Switched to a new branch 'test'

$ vim file1.md // make some changes

$ git add file1.md

$ git commit -m "Committing changed to file1.md"

$ git checkout main // switch to main

$ git merge test // merge changes from test

Updating 09e1947..ebb5838

Fast-forward

file1.md | 136 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

1 file changed, 118 insertions(+), 18 deletions(-)

$ git branch -d test // remove branch (optional)

Deleted branch test (was ebb5838).

When you merge, Git examines your copy of each file, and attempts to apply any other changes that may have been committed to main since you created the branch. In many cases, as long as there are no conflicts, Git will merge the changes together. However, if Git is unable to do so, then you will be prompted to manually merge the changes together.

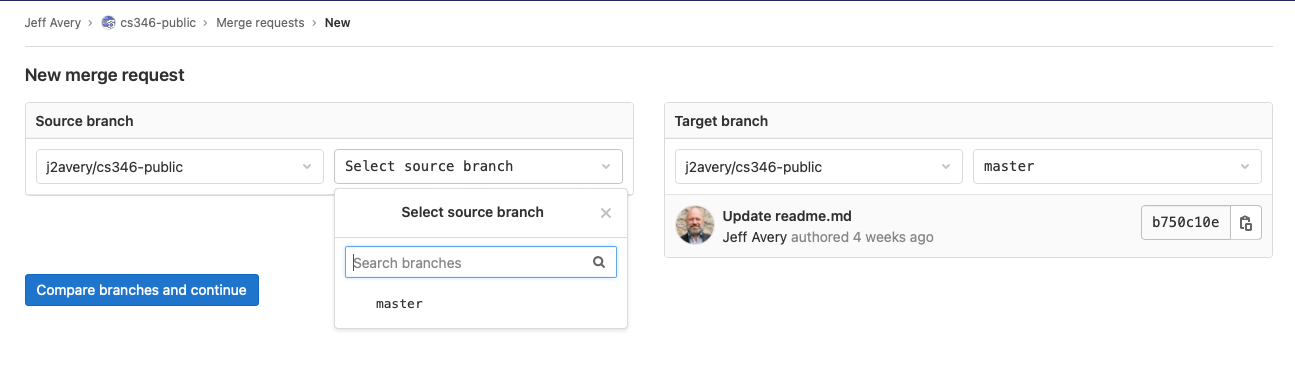

Pull requests (PRs)

One way to avoid merge issues is to review changes before they are merged into main (this also lets you review the code, manually run tests etc). The standard mechanism for this is a Pull Request (PR). A PR is simply a request to another developer (possibly the person responsible for maintaining the main branch) to git pull your feature branch and review it before merging.

We will not force PRs in this course, but you might find them useful within your team.

GitLab also calls these Merge Requests.

Last Word