Mobile development

Design

Smartphones and tablets are considered to be mobile devices running a graphical user interface. There are some caveats when comparing desktop and mobile applications:

- Mobile applications are smaller, obviously, since they tend to be designed for hand-held devices (and not large computer screens).

- Mobile applications use multi-touch as a primary input mechanism. These applications might support keyboard input, but it’s secondary to touch.

- Applications are typically run full-screen, and most mobile operating systems do not support windowed applications.

Mobile devices often have similar graphical and processing capabilities and low-end notebook or desktop computers; the limits on these devices are often related to the challenge of interacting with a rich UI on a small screen.

You should expect most interaction to consist of multi-touch gestures or on-screen actions that you perform. The following are common gestures:

- Press: select the target under the point of contact and activate it (i.e. analogous to single-click with a mouse)

- Long-press: equivilent to right-clicking on an element.

- Swipe: move or translate content.

- Tap-swipe: move a chunk e.g. page up or page down.

- Pinch/zoom: change the scale of the content.

For text entry and manipulation, you should support a soft keyboard (i.e. on-screen). Do not assume that the user has a physical keyboard connected. When possible show a keyboard optimized for region and data that you’re collecting e.g. a numeric keyboard for entering phone numbers.

Do not assume mouse or stylus, except under very specific circumstances where you know they will exist. e.g. building a drawing application optimized for a stylus.

Challenges that are unique to mobile devices:

- Given the screen size issues, menus are a bad idea. Widgets should be considerably larger than they would be on desktop to support touch interaction.

- Keyboard support is limited. Mobile devices tend to rely on “soft” on-screen keyboards. On-screen keyboards lack tactile feedback, are slower and less accurate than physical keyboards.

- The configuration of a mobile device can change dynamically e.g. rotating the device from vertical to horizontal generally causes the screen to “rotate” to match the new configuration.

Project Setup

Android projects are complex; much of the framework is imported as libraries. With Android development, it’s highly recommended that you use the New Project wizard to create your starting project.

Create a new project

We’ll assume that you have Android Studio installed. See Toolchain installation for setup details.

In Android Studio, select File > New > New Project. This will launch the New Project Wizard. Choose the Empty Activity project, and keep default settings. This will generate a Hello World style application.

After the project finishes loading, continue to the next step.

Install a virtual device

With mobile development, it’s quite common to use virtual devices for testing instead of needing one or more physical phones.

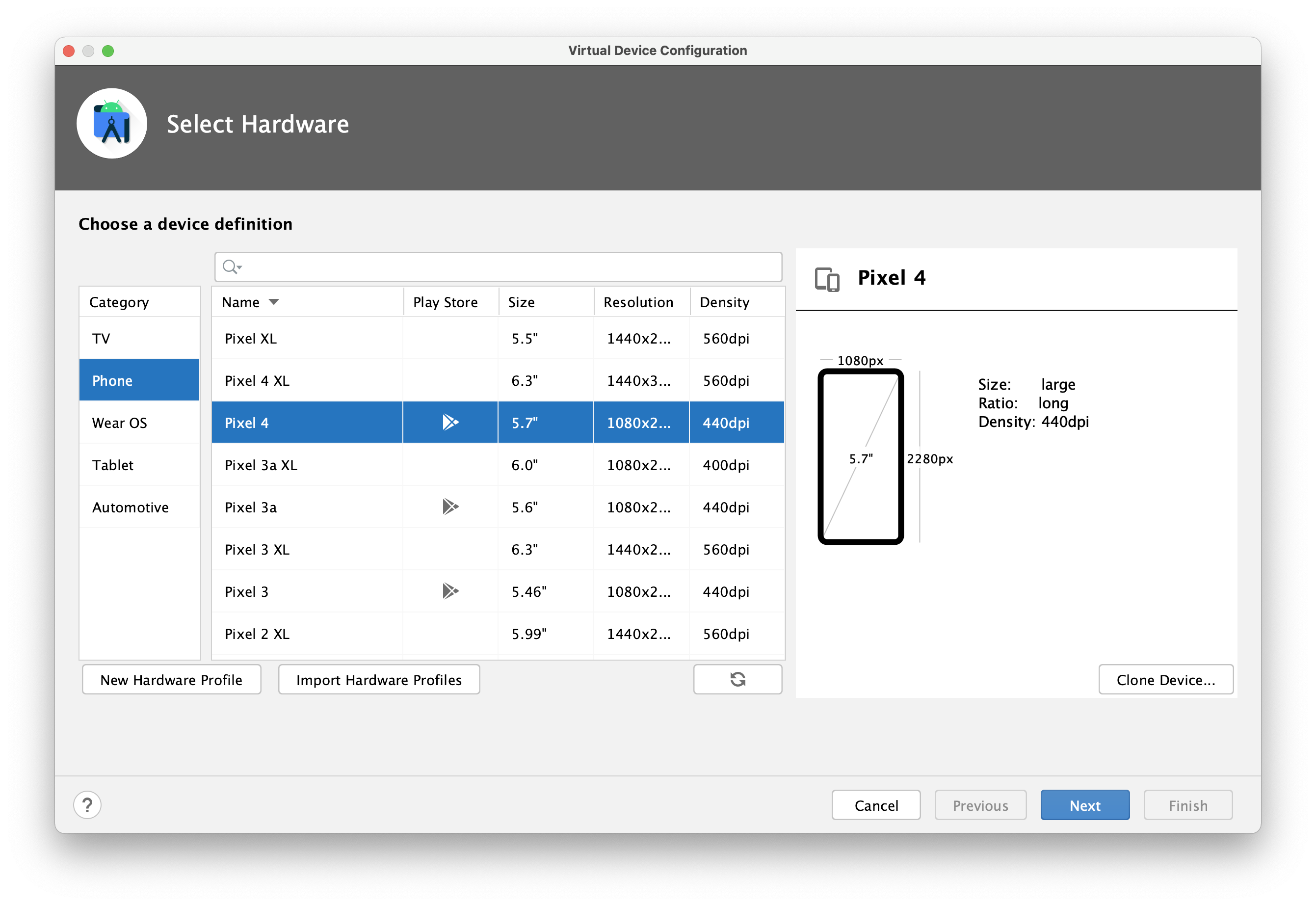

You can setup a virtual device in the IDE under: Tools > Android > Device Manager.

Choose a standard device1 and click Next through the dialog options, selecting defaults. Make sure to pick an image that your hardware supports (i.e. x86 or arm as appropriate).

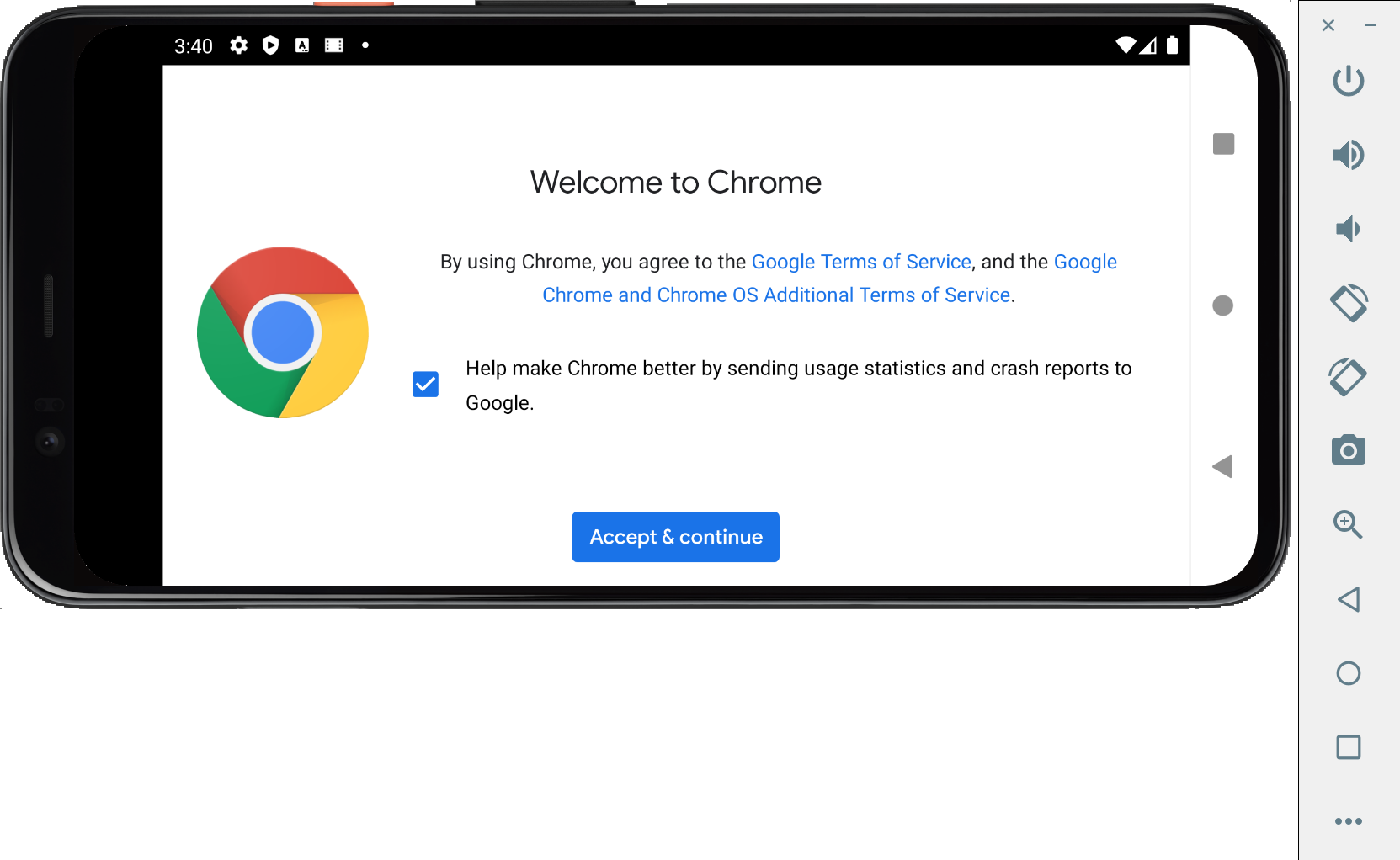

To run the device, click on the Power button and it should power up! By default, the IDE will install and run your application on this virtual device. Below, you can see an example of us running the Chrome browser on the AVD.

Compile and package

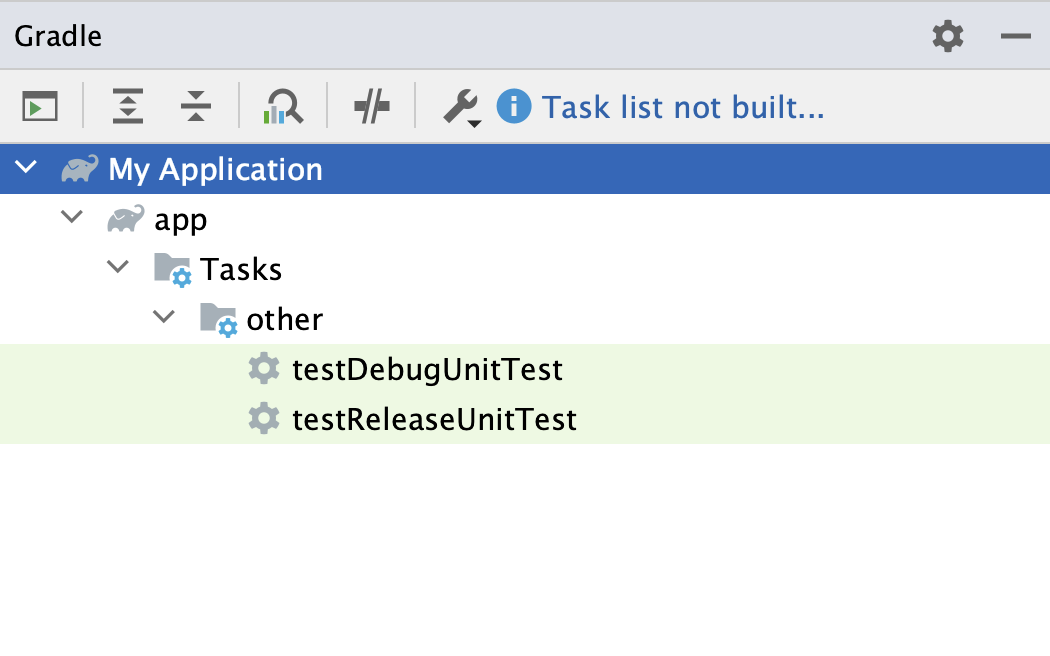

Android projects use Gradle, with the standard Gradle project configuration. However, for performance reasons, Android Studio doesn’t populate or update the Gradle tasks lists automatically. For that reason, the Gradle menu appears mostly empty.

Instead of using the Gradle menu, rely instead on the Build and Run menus:

| Command | What does it do? |

|---|---|

Build > Make project | Builds your project (incrementally) |

Build > Clean project | Removes temp files (deletes the build directory) |

Build > Rebuild project | Completely rebuilds your project |

Run > Run app | Runs your application on either an attached device, or an emulator. |

tWhen you build an Android executable, it compiles your code along with any required data or resources files into an APK file, an archive file with an .apk suffix. This is installed on the device automatically by the IDE when you run the application.

Project structure

Android uses Gradle, so the project structure should look similiar to earlier projects. Expand the Project folder (CMD-1 or Ctrl-1) to see the contents of the project.

src folder (source code)

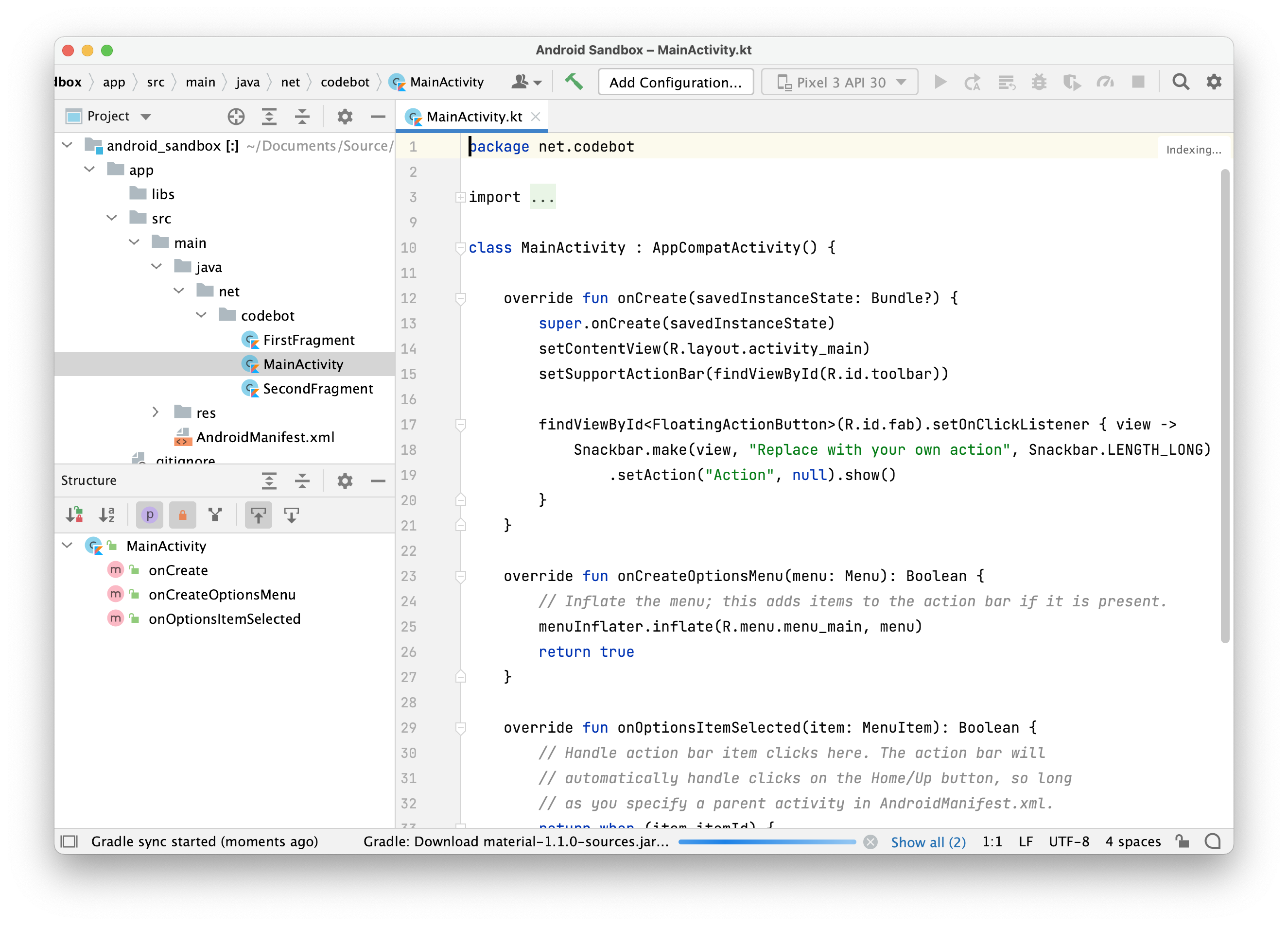

The src folder contains source code, nested into a directory structure that matches the package name of your classes. In the example above, src/main/java is the top level source code folder, and net.codebot is the package name. FirstFragment, MainActivity and SecondFragment are classes that exist in this project.

res folder (resources)

A resource in Android refers to any non-code assets that you project uses. This includes:

- icons and other image files that your application might use

- sound clips, or any other media asset

- configuration files, databases, or other file types

Android has a mechanism for deadling with resources in code that is extremely helpful. If you follow this process, Gradle can automatically bundle resources with your application when it’s packaged. This mechanism also removes the need for to interact with file system directly.

Resources are stored in a project until the /res folder. Here’s an example of a project structure with default resources.

src

└── main

├── AndroidManifest.xml

├── java

│ └── org

└── res

├── drawable

├── mipmap-anydpi

├── mipmap-hdpi

├── mipmap-mdpi

├── mipmap-xhdpi

├── mipmap-xxhdpi

├── mipmap-xxxhdpi

├── values

└── xml

The source code is under src/main/java/org, and the default resource directory structure is under src/main/res.

drawablewould typically contains images.mipmapis a set of folders containing the application icon, scaled to different resolutions (the OS will choose the suitable one at runtime based on device characteristics).valuescontains constants, defined in XML files.

For example, here’s the contents of values/strings.xml:

<resources>

<string name="app_name">Toast</string>

</resources>

On Android, all constants should be stored in XML files, in this directory structure. This isolated strings and other constant values and makes it easier to update them when doing localization or other customizations.

Layout XML files can also be placed in the res folder structure, to describe layouts for the old-style view classes. We don’t use layout files in Compose, so you can safely ignore those.

When you compile your application, resources are converted to unique IDs, which you can then reference in code to fetch the corresponding resource e.g., the “app_name” string from the strings.xml resource file would be referred to in code as R.string.app_name, and we can lookup that ID to find the corresponding resource

setContent {

ToastTheme {

Scaffold { padding ->

App(activity = this,

title=getResources().getString(R.string.app_name), // passing in the string resource

modifier = Modifier.padding(padding))

}

}

}

You can easily add resources to your application by just copying them into the res folder structure. Your also has a built-in library of vector images that you can use and customize. File > New > Vector Asset and click on the Clip art button to browse. (Images are all free to use and licensed under Apache license 2.0).

Manifest

The AndroidManifest.xml file is generated with your project; one is reproduced below. This file contains settings that tell the application how to present itself on Android e.g. icon, label, theme. The activity element tells is which class to launch when the application launches. Other permissions and settings can be added in here as-needed.

You should be very careful when modifying this file! If you remove critical settings, or break the formatting, your project may not build.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

package="net.codebot">

<application

android:allowBackup="true"

android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:roundIcon="@mipmap/ic_launcher_round"

android:supportsRtl="true"

android:theme="@style/Theme.AndroidSandbox">

<activity

android:name=".MainActivity"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:theme="@style/Theme.AndroidSandbox.NoActionBar">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER"/>

</intent-filter>

</activity>

</application>

</manifest>

Architecture

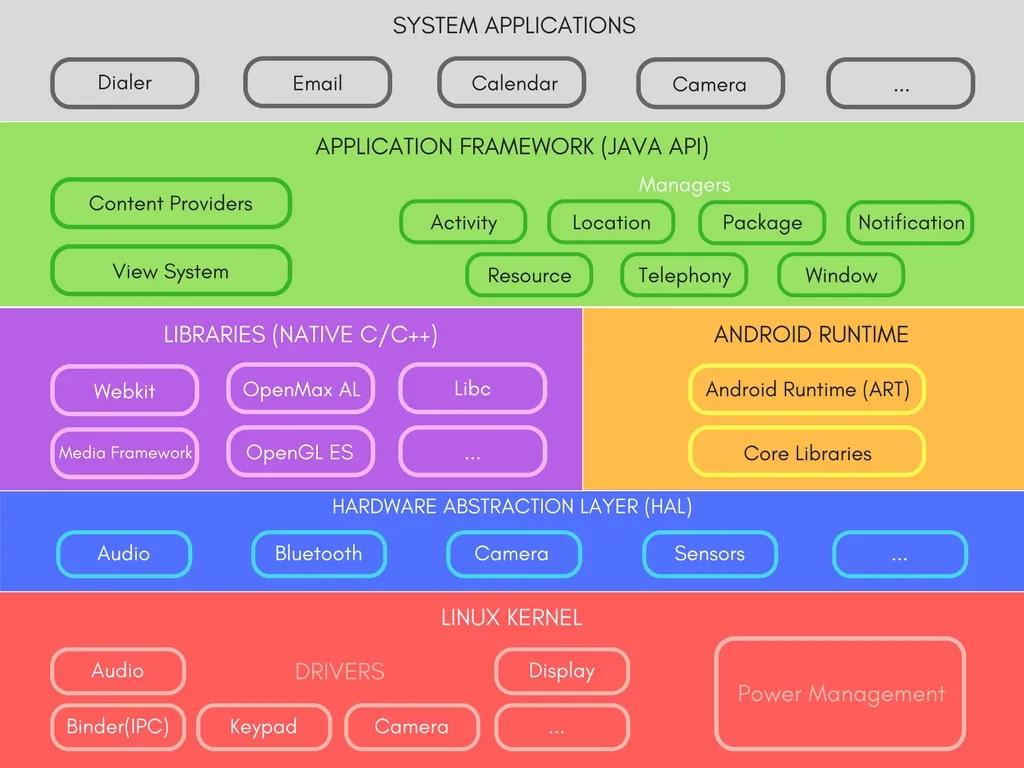

Android is an open-source, Linux based operating system designed to run across a variety of devices and form-factors. It’s an example of a layered architecture, which increasing levels of abstraction as we move from the low-level hardware to higher-level application APIs. Mid-level components exist to provide services to components futher up the stack.

https://developer.android.com/guide/platform

As a developer, the entire feature-set of the Android OS is available to you through APIs written in Java and/or Kotlin2. These APIs form the building blocks you need to create Android apps by providing critical services: :

- A rich and extensible View System you can use to build an app’s UI, including lists, grids, text boxes, buttons, and even an embeddable web browser

- A Resource Manager, providing access to non-code resources such as localized strings, graphics, and layout files

- A Notification Manager that enables all apps to display custom alerts in the status bar

- An Activity Manager that manages the lifecycle of apps and provides a common navigation back stack

- Content Providers that enable apps to access data from other apps, such as the Contacts app, or to share their own data

Android also includes a set of core runtime libraries that provide most of the functionality of the Java programming language, including some Java 8 language features, that the Java API framework uses.

For devices running Android version 5.0 (API level 21) or higher, each app runs in its own process and with its own instance of the Android Runtime (ART). ART is written to run multiple virtual machines on low-memory devices by executing DEX files. ART provides Ahead-of-time (AOT) and just-in-time (JIT) compilation, and Optimized garbage collection (GC) to the platform3.

Components

There are four different types of core components that can be created in Android. Each represents a different style of application, with a different entry point and lifecycle.

These four component types exist in Android:

- An Activity is an Android class that represent a single screen. It handles drawing the user interface (UI) and managing input events. An application may include multiple activities, where one is the “entry point”.

- A Service is a general-purpose background service, representing some long-running operation that the OS should perform, which does not require a user-interface. e.g. a music playback service.

- Broadcast Receivers: A service that can launch itself in response to a system event, without the need to stay running in the background like a regular service. e.g. an application to pop up a reminder when the user arrives at a destination.

- Content Providers managed shared information that other services or applications can access. e.g. a shared contact database.

Activities

Activities are the most common type of component, since they include user interfaces and visible components.

Typically one activity will be the “main” activity that represents the entry point when your application launches.

There are a standard set of steps that occur when your Android application launches. The system uses the information in the AndroidManifest.xml to determine which activity to launch, and how to launch it. In this case, it’s a class named MainActivity:

<activity

android:name=".MainActivity"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:theme="@style/Theme.AndroidSandbox.NoActionBar">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER"/>

</intent-filter>

</activity>

The MainActivity is a class that extends AppCompatActivity. This is a base class that supports all modern Android features while providing backward compatibility with older versions of Android. For compatibility with older version of Android, you should always use AppCompatActivity as a base class.

Our base class contains a number of methods. The onCreate() method is the first method that is called when the MainActivity is instantiated. Here’s a basic onCreate() method:

class MainActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main) // layout file using view classes

// ...

}

}

Activities typically have an associated layout file which describes their appearance. The activity and the layout are connected by a process known as layout inflation. When the activity starts, the views that are defined in the XML layout files are turned into (or “inflated” into) Kotlin view objects in memory. Once this happens, the activity can draw these objects to the screen and dynamically modify them.

R.layout.activity_main in this example corresponds to the layout/activity_main.xml file. That file contains the full layout for the screen, including the top toolbar. There are multiple pieces to this particular layout, so the line <include layout="@layout/content_main"/> is including the contents of a second layout file (just split up to make it easier to manage).

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<androidx.coordinatorlayout.widget.CoordinatorLayout

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:app="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res-auto"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

tools:context=".MainActivity">

<com.google.android.material.appbar.AppBarLayout

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:theme="@style/Theme.AndroidSandbox.AppBarOverlay">

<androidx.appcompat.widget.Toolbar

android:id="@+id/toolbar"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="?attr/actionBarSize"

android:background="?attr/colorPrimary"

app:popupTheme="@style/Theme.AndroidSandbox.PopupOverlay"/>

</com.google.android.material.appbar.AppBarLayout>

<include layout="@layout/content_main"/>

<com.google.android.material.floatingactionbutton.FloatingActionButton

android:id="@+id/fab"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:layout_gravity="bottom|end"

android:layout_margin="@dimen/fab_margin"

app:srcCompat="@android:drawable/ic_dialog_email"/>

</androidx.coordinatorlayout.widget.CoordinatorLayout>

Lifecycle

Applications consist of one or more running activities, each one corresponding to a screen.

Activities in the system are managed as activity stacks. When a new activity is started, it is usually placed on the top of the current stack and becomes the running activity – the previous activity always remains below it in the stack, and will not come to the foreground again until the new activity exits.

An activity can be one of the following running states:

- The activity in the foreground, typically the one that user is able to interact with, is running.

- An activity that has lost focus but can still be seen is visible. It will remain active.

- An activity that is completely hidden, or minimized is stopped. It retains its state (it’s basically paused) BUT the OS may choose to terminate it to free up resources.

- The OS can choose to destroy an application to free up resources.

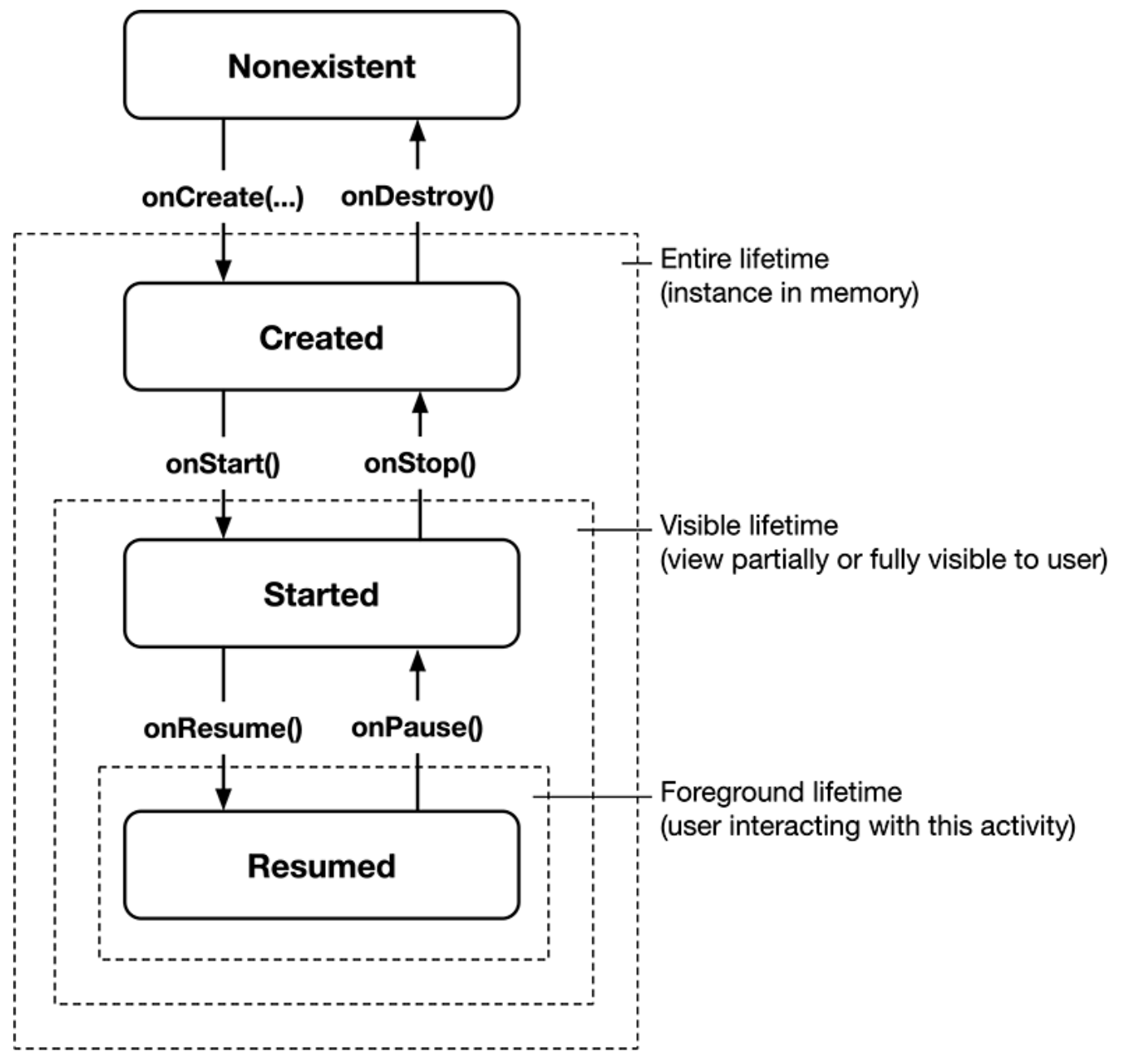

This diagram shows the Android activity lifecycle, with all potential activity states.

These phases each have corresponding callback methods that get called when the activity enters that state. You can override a method in your Activity to add code that will get executed at that time:

public class Activity extends ApplicationContext {

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState);

protected void onStart();

protected void onRestart();

protected void onResume();

protected void onPause();

protected void onStop();

protected void onDestroy();

}

There are three key loops that these phases attempt to capture:

-

The entire lifetime of an activity happens between the first call to

onCreate(Bundle)through to a single final call toonDestroy(). An activity will do all setup of “global” state in onCreate(), and release all remaining resources in onDestroy(). For example, if it has a thread running in the background to download data from the network, it may create that thread in onCreate() and then stop the thread in onDestroy(). -

The visible lifetime of an activity happens between a call to

onStart()until a corresponding call toonStop(). During this time the user can see the activity on-screen, though it may not be in the foreground and interacting with the user. Between these two methods you can maintain resources that are needed to show the activity to the user. For example, you can register aBroadcastReceiverin onStart() to monitor for changes that impact your UI, and unregister it in onStop() when the user no longer sees what you are displaying. The onStart() and onStop() methods can be called multiple times, as the activity becomes visible and hidden to the user. -

The foreground lifetime of an activity happens between a call to

onResume()until a corresponding call toonPause(). During this time the activity is in visible, active and interacting with the user. An activity can frequently go between the resumed and paused states – for example when the device goes to sleep, when an activity result is delivered, when a new intent is delivered – so the code in these methods should be fairly lightweight.https://developer.android.com/reference/android/app/Activity#Fragments

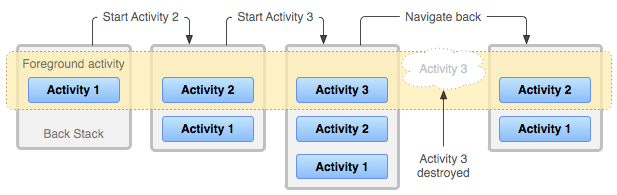

Activity Stack

A task is a collection of activities that users interact with when performing a certain job. The activities are arranged in a stack — the back stack — in the order in which each activity is opened. For example, an email app might have one activity to show a list of new messages. When the user selects a message, a new activity opens to view that message. This new activity is added to the back stack. If the user presses the Back button, that new activity is finished and popped off the stack.

The device Home screen is the starting place for most tasks. When the user touches an icon in the app launcher (or a shortcut on the Home screen), that app’s task comes to the foreground. If no task exists for the app (the app has not been used recently), then a new task is created and the “main” activity for that app opens as the root activity in the stack.

The device Home screen is the starting place for most tasks. When the user touches an icon in the app launcher (or a shortcut on the Home screen), that app’s task comes to the foreground. If no task exists for the app (the app has not been used recently), then a new task is created and the “main” activity for that app opens as the root activity in the stack.

When the current activity starts another, the new activity is pushed on the top of the stack and takes focus. The previous activity remains in the stack, but is stopped. When an activity stops, the system retains the current state of its user interface. When the user presses the Back button, the current activity is popped from the top of the stack (the activity is destroyed) and the previous activity resumes (the previous state of its UI is restored). Activities in the stack are never rearranged, only pushed and popped from the stack—pushed onto the stack when started by the current activity and popped off when the user leaves it using the Back button. As such, the back stack operates as a “last in, first out” object structure.

If the user continues to press Back, then each activity in the stack is popped off to reveal the previous one, until the user returns to the Home screen (or to whichever activity was running when the task began). When all activities are removed from the stack, the task no longer exists.

This is standard behaviour for most applications. For unusual workflows, you can manually manage tasks.

Intents

An intent is an asynchronous message, that represents an an operation to be performed. This can include activating components, or activities. An intent is created with an Intent object, which defines a message to activate either a specific component (explicit intent) or a specific type of component (implicit intent).

Applications then, consist of a number of different component working together. Some of them you will create, and some are preexisting components that you can activate (e.g. you can create an intent requesting that the camera take a picture; you don’t need to write code to make that happen, you just need to use the intent to ask someone else to take it for you and return the data).

ViewModel

One major challenge with the Activity model is that activities lose state when they are unload. How can this possibly work? You don’t want to lose all of your data every time you need to change screens. There’s numerous ways to address this, including saving data to a bundle, or manually persisting to a data store. Jetpack Compose introduces classes to manage this for us.

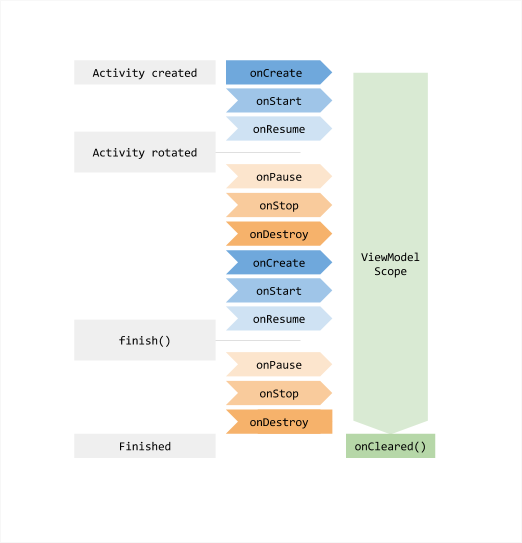

The ViewModel class is designed to store and manage UI-related data in a lifecycle conscious way. The ViewModelclass allows data to survive configuration changes such as screen rotations.

Best-practice is to move your application data into ViewModels and use them as the main container classes. Not only will your data survive orientation changes and activity swapping, but the ViewModel works well with other Jetpack libraries like Compose (for user interfaces).

From the implementation notes

Architecture Components provides a ViewModel helper class for the UI controller that is responsible for preparing data for the UI. ViewModel objects are automatically retained during configuration changes so that data they hold is immediately available to the next activity or fragment instance. For example, if you need to display a list of users in your app, make sure to assign responsibility to acquire and keep the list of users to a ViewModel, instead of an activity or fragment.

class MyViewModel : ViewModel() {

private val users: MutableLiveData<List<User>> by lazy {

MutableLiveData<List<User>>().also {

loadUsers()

}

}

fun getUsers(): LiveData<List<User>> {

return users

}

private fun loadUsers() {

// Do an asynchronous operation to fetch users.

}

}

You can then access the list from an activity as follows:

class MyActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

// Create a ViewModel the first time the system calls an activity's onCreate() method.

// Re-created activities receive the same MyViewModel instance created by the first activity.

// Use the 'by viewModels()' Kotlin property delegate

// from the activity-ktx artifact

val model: MyViewModel by viewModels()

model.getUsers().observe(this, Observer<List<User>>{ users ->

// update UI

})

}

}

If the activity is re-created, it receives the same MyViewModel instance that was created by the first activity. When the owner activity is finished, the framework calls the ViewModel objects’s onCleared() method so that it can clean up resources.

Lifecycle

ViewModel objects are scoped to the Lifecycle passed to the ViewModelProvider when getting the ViewModel. The ViewModel remains in memory until the Lifecycle it’s scoped to goes away permanently: in the case of an activity, when it finishes, while in the case of a fragment, when it’s detached.

The figure below illustrates the various lifecycle states of an activity as it undergoes a rotation and then is finished. The illustration also shows the lifetime of the ViewModel next to the associated activity lifecycle. This particular diagram illustrates the states of an activity. The same basic states apply to the lifecycle of a fragment.

Features

Creating a main method

Android projects are structured differently from desktop projects. Instead of a main method, you have a main Activity class. Think of an activity as a single screen, and the main Activity is the screen that launches with the application. The onCreate() method is the entry point for your main Activity, and the method that we will override to set up our application.

Here is the starter code that is generated:

class MainActivity : ComponentActivity() {

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

setContent {

MyApplicationTheme {

// A surface container using the 'background' color from the theme

Surface(

modifier = Modifier.fillMaxSize(),

color = MaterialTheme.colorScheme.background

) {

Greeting("Android")

}

}

}

}

}

@Composable

fun Greeting(name: String, modifier: Modifier = Modifier) {

Text(

text = "Hello $name!",

modifier = modifier

)

}

This basic structure does the following:

class MainActivityis just defining the activity class that we’ll use.override fun onCreate()is the callback function that we’ll override. This gets called when the application is launched.setContent()is a scoping function that defines our composable scope! Composables can be called from within this function.MyApplicationThemeis just an override of theMaterialThemeclass (Android expects you to customize it by default).Surfaceis a composable layout that we can use to hold our other composables.

The rest of the structure should look familiar, since it’s all just Compose! You should be able to swap out everything in the setContent block with Compose code that you write.

Launching an activity

Intents can be used to activate an Activity. The startActivity(Intent) method is used to start a new activity, which will be placed at the top of the activity stack. It takes a single argument, an Intent, which describes the activity to be executed. To be of use with Context.startActivity(), all activity classes must have a corresponding <activity>declaration in their package’s AndroidManifest.xml.

Sometimes you want to get a result back from an activity when it ends. For example, you may start an activity that lets the user pick a person in a list of contacts; when it ends, it returns the person that was selected. To do this, you call the startActivityForResult(Intent, int) version with a second integer parameter identifying the call. The result will come back through your onActivityResult(int, int, Intent)method.

Building a user interface

Compose user interface code is typically invoked from your application’s MainActivity class. From your onCreate() method, you call setContent { } to setup your user interface.

We cover building and displaying user interfaces in the user interfaces section.

class MainActivity : ComponentActivity() {

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

setContent {

// user interface code goes here

Text("Hello World")

}

}

Navigating between activities

Navigation refers to the ability to move between screens or activities within an application. This includes simple scenarios e.g., click a button to navigate, to complex cases like the Android navigation drawer.

The Navigation classes were originally designed to work with fragments (you can think of them as pieces of a UI), which have since been superceded by Jetpack Compose. We’ll discuss using these classes on Android, assuming Jetpack Compose.

The built-in navigation classes are only fully supported on Android, not Compose Multiplatform/Desktop. If you are working with Compose Multiplatform, or want something that feels a little more “idiomatic”, you might consider a third-party navigation library instead e.g., Voyager.

There are three components that work together:

- Navigation graph - resource i.e. XML file that defines routes.

- NavHost - UI element that contains the current navigation destination.

- NavController - Coordinator for managing navigation.

Best practices for working within Compose is to create a single activity, and then use navigation components to tear-down and build-up the single activity to reflect how you want the screen to appear.

Here’s the steps you would take to use the Navigation components:

Step 1: Create a navigation controller

To create a NavController when using Jetpack Compose, call rememberNavController():

val navController = rememberNavController()

Step 2: Create a navigation graph

The nav graph is just a data structure that holds our routes between screens. Since this is Compose, we’ll create everything programatically.

@Serializable

object Profile

@Serializable

object FriendsList

val navController = rememberNavController()

NavHost(navController = navController, startDestination = Profile) {

composable<Profile> { ProfileScreen( /* ... */ ) }

composable<FriendsList> { FriendsListScreen( /* ... */ ) }

// Add more destinations similarly.

}

If you need to pass data to a destination, define the route with a class that has parameters. For example, the Profile route is a data class with a name parameter.

@Serializable

data class Profile(val name: String)

Step 3: Navigate to a destination

To navigate to a composable, you should use NavController.navigate<T>. With this overload, navigate() takes a single route argument for which you pass a type. It serves as the key to a destination.

@Serializable

object FriendsList

navController.navigate(route = FriendsList)

Android Developer Relations has published an excellent codelab, which will help you learn how to use Jetpack Navigation. See this page to get started.

Packaging & Installers

Mobile applications are typically distributed through an online store e.g., Google Play or the Apple App Store. As interesting as this is, it’s beyond the scope of what we can accomplish in this course.

For the purposes of this course, if you are developing for Android, you can product a local binary (an APK file) that can be installed in an emulator.

In IntelliJ or Android Studio:

Build > Generate App Bundle (APK) > Generate APK.