Design principles

Now that we’ve discussed high-level principles of software architecture, we should review lower-level concerns aka design issues. Let’s start by reviewing SOLID principles.

SOLID principles

SOLID was introduced by Robert (“Uncle Bob”) Martin around 2002. Some ideas were inspired by other practitioners, but he was the first to codify them.

The SOLID Principles tell us how to arrange our functions and data structures into classes, and how those classes should be interconnected. The goal of the principles is the creation of mid-level software structures that:

- Tolerate change (extensibility),

- Are easy to understand (readability), and

- Are the basis of components that can be used in many software systems (reusability).

If there is one principle that Martin emphasizes, it’s the notion that software is ever-changing. There are always bugs to fix, features to add. In his approach, a well-architected system has features that facilitate rapid but reliable change.

The SOLID principles are as follows. The diagrams and examples are from Ugonna Thelma’s Medium post “The S.O.L.I.D. Principles in Pictures.”

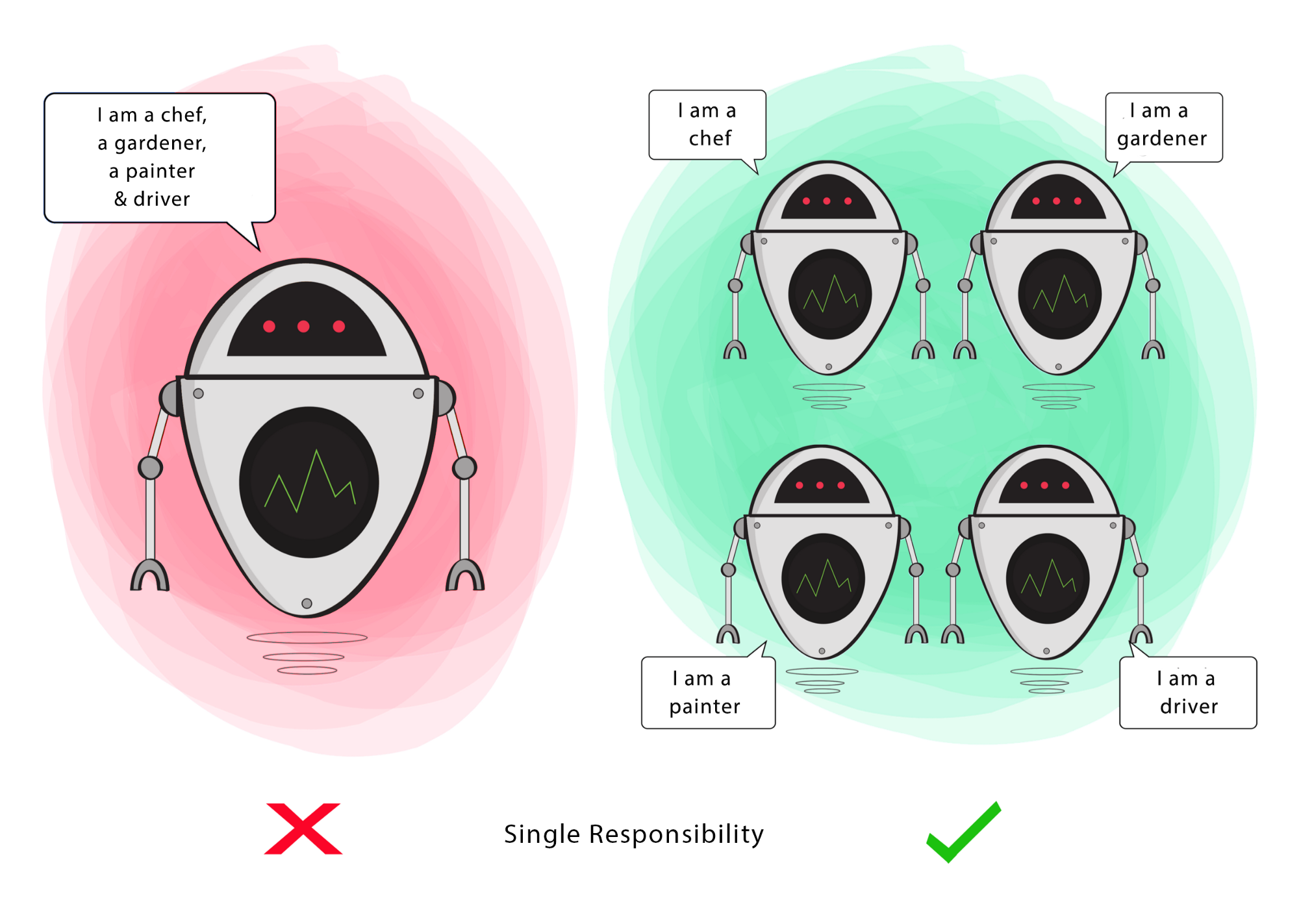

1. Single Responsibility

“A module should be responsible to one, and only one, user or stakeholder.”

– Robert C. Martin (2002)

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) claims to result in code that is easier to maintain. The principle states that we want classes to do a single thing. This is meant to ensure that are classes are focused, but also to reduce pressure to expand or change that class. In other words:

- A class has responsibility over a single functionality.

- There is only one single reason for a class to change.

- There should only be one “driver” of change for a module.

Single-responsibility can also apply to a module, or component or any other unit. Cohesion!

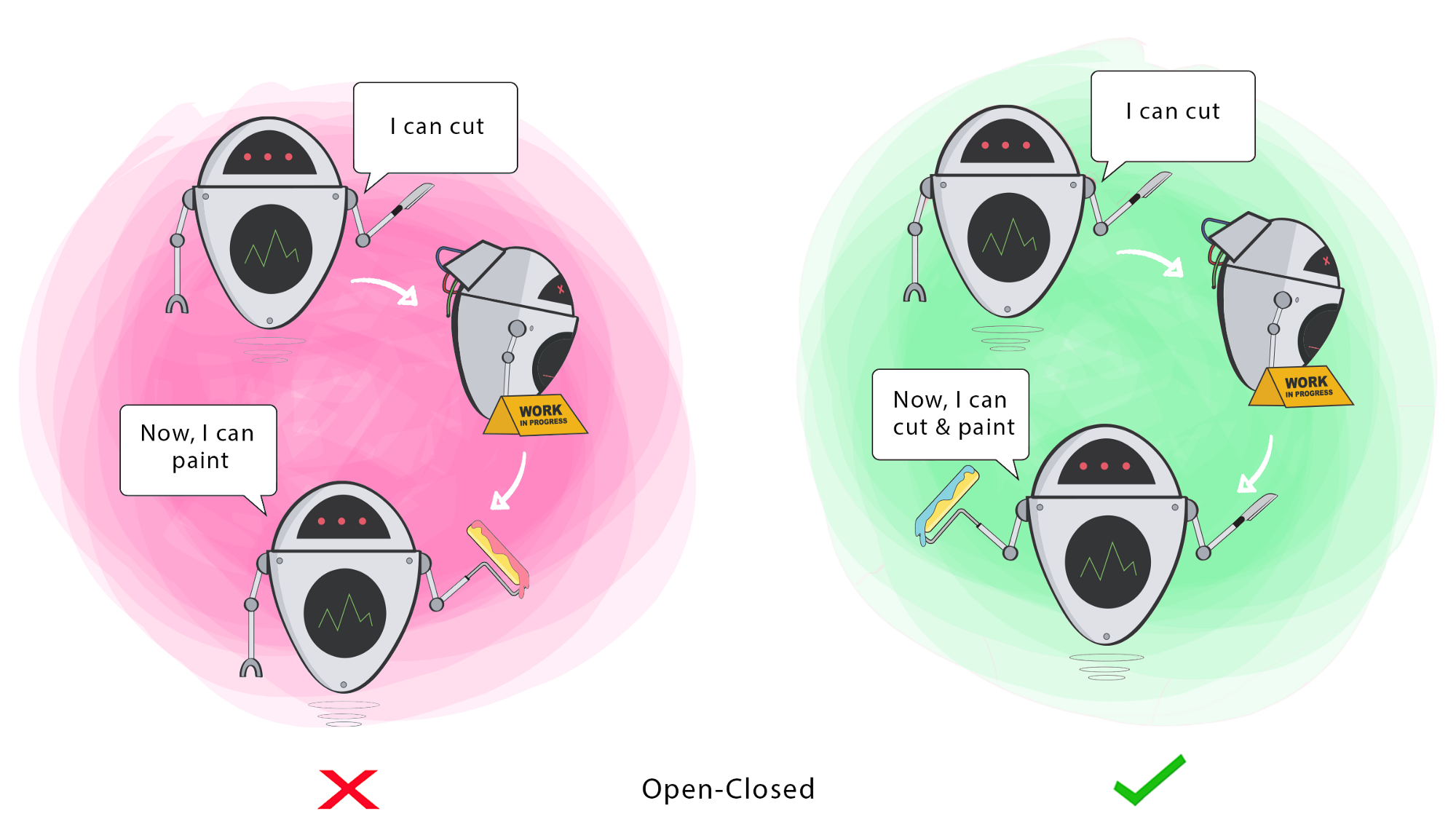

2. Open-Closed Principle

“A software artifact should be open for extension but closed for modification. In other words, the behavior of a software artifact ought to be extensible, without having to modify that artifact.” – Bertrand Meyers (1988)

This principle champions sub-classing as the primary form of code reuse.

- A particular module (or class) should be reusable without needing to change its implementation.

- Often used to justify class hierarchies (i.e. derive to specialize).

This principle is also warning against changing classes in a hierarchy, since any behavior changes will also be inherited by that class’s children! In other words, if you need different behavior, create a new subclass and leave the existing classes alone.

The Design Pattern principle of Composition over inheritance runs counter to this, suggesting instead that code reuse through composition is often more suitable.

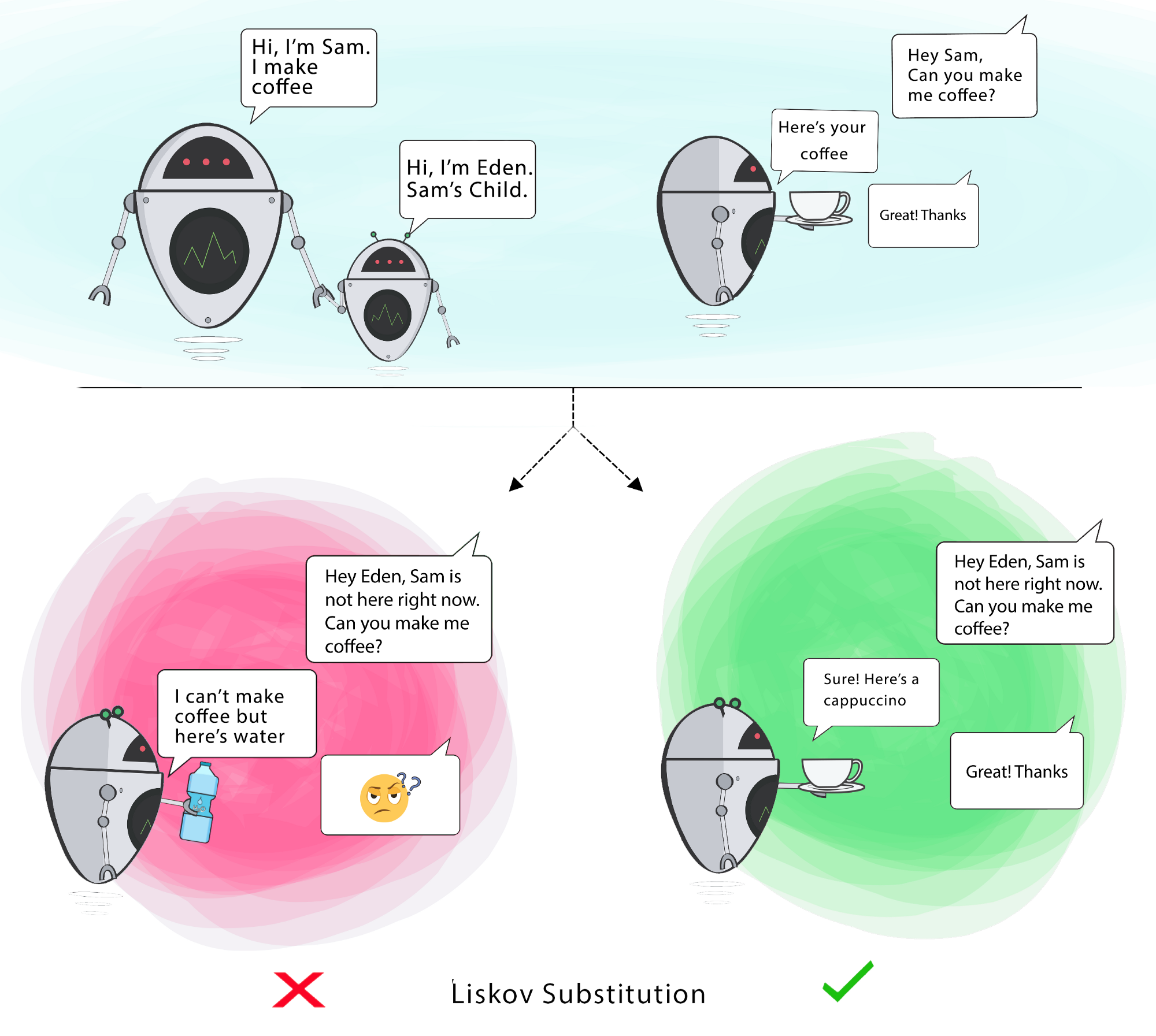

3. Liskov-Substitution Principle

“If for each object o1 of type S there is an object o2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behaviour of P is unchanged when o1 is substituted for o2, then S is a subtype of T.” – Barbara Liskov (1988)

It should be possible to substitute a derived class for a base class, since the derived class should still be capable of all the base class functionality. In other words, a child should always be able to substitute for its parent.

In the example below, if Sam can make coffee but Eden cannot, then you’ve modelled the wrong relationship between them.

Don’t get hung up on the “subclass” part of this principle. It applies to any type-of relationships. Remember interfaces? They effectively act as a

super-typeby specifying behaviors that all of their concretions promise to implement.

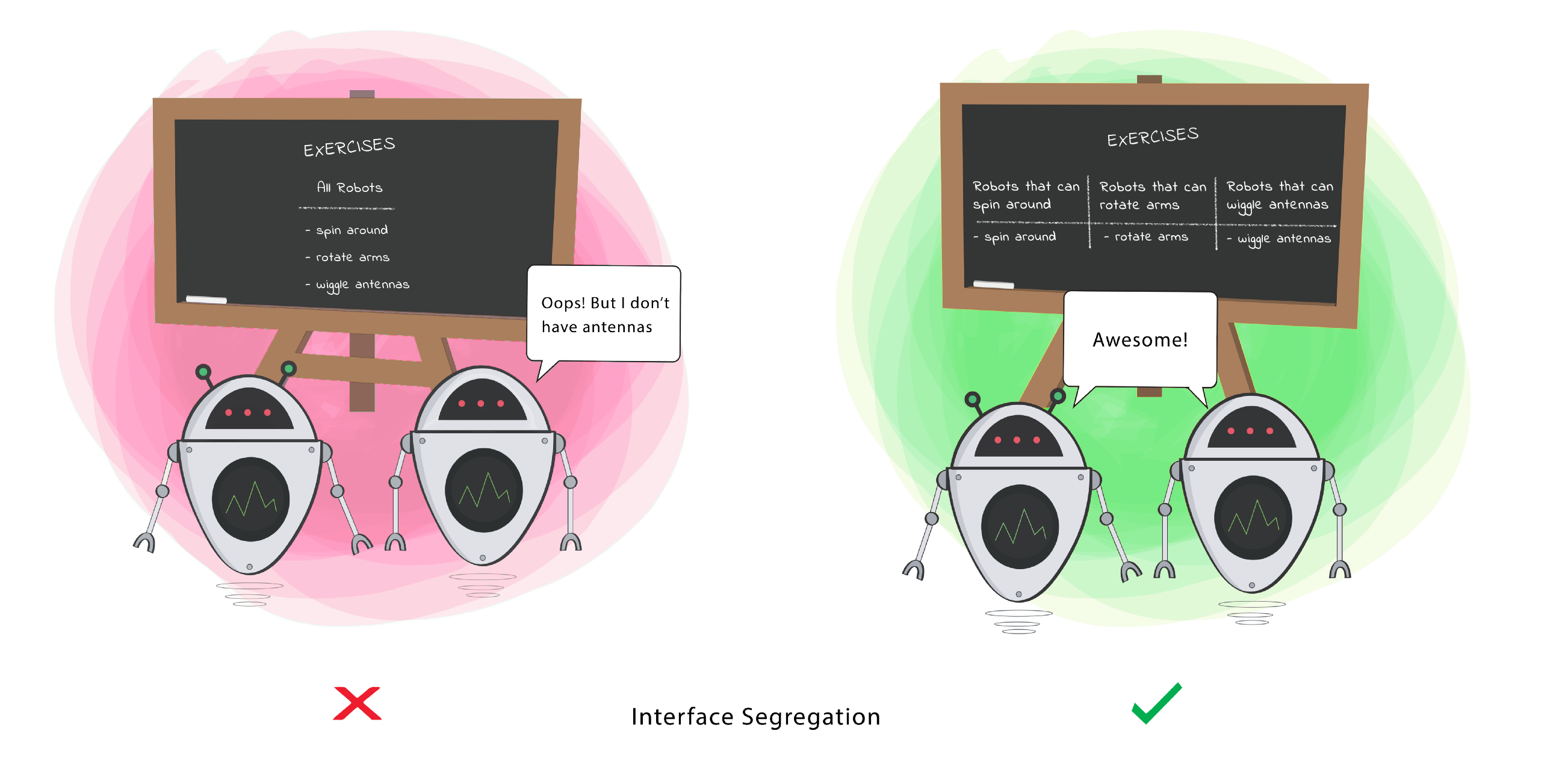

4. Interface Substitution

It should be possible to substitute classes based on their interface; behavior should be independently of the implementation classes.

Also described as “program to an interface, not an implementation.” This means focusing your design on what the code is doing, not how it does it. Never make assumptions about what the underlying code is doing—if you code to the interface, it allows flexibility, and the ability to substitute other valid implementations that meet the functional needs.

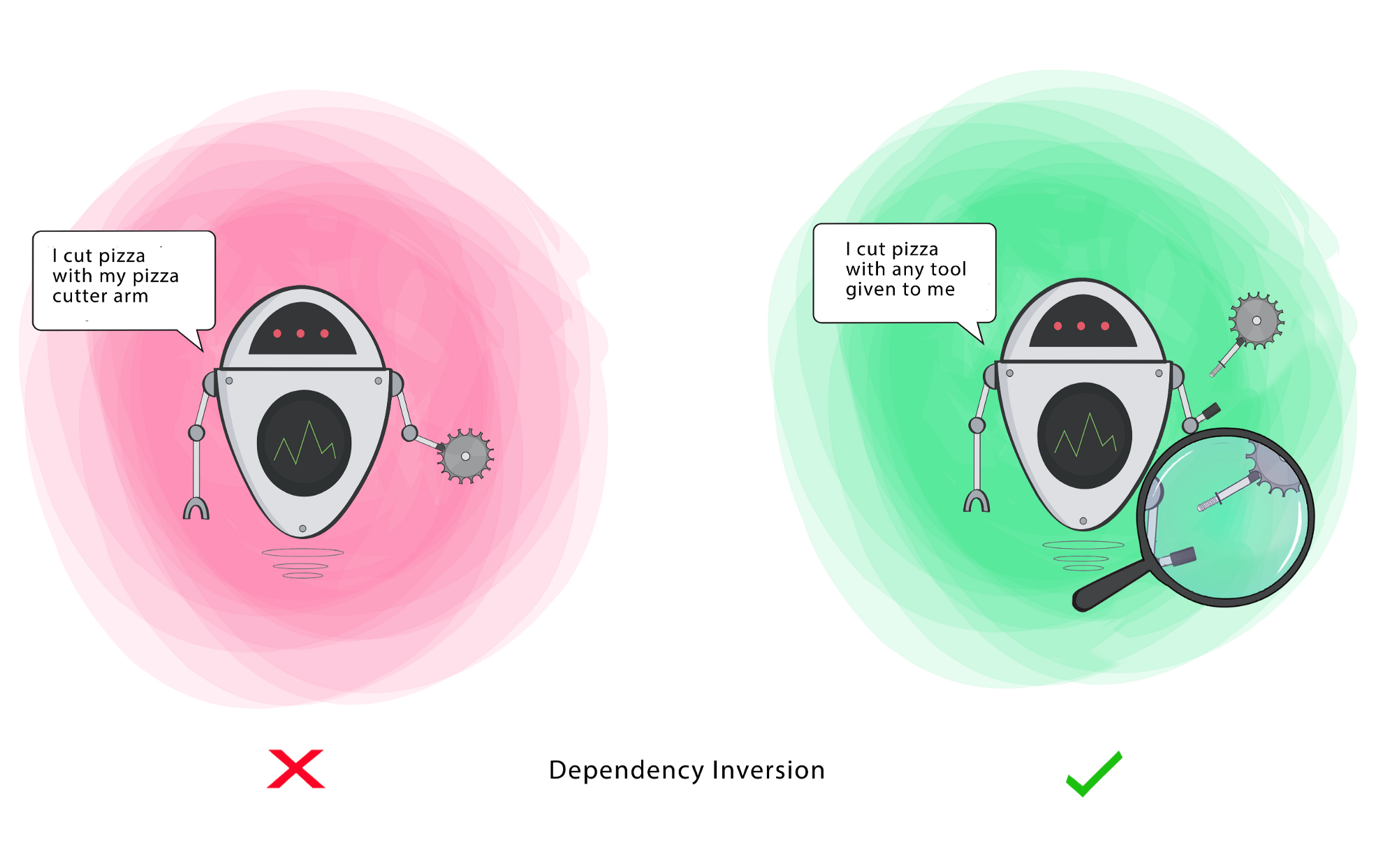

5. Dependency Inversion Principle

The most flexible systems are those in which source code dependencies refer to abstractions (interfaces) rather than concretions (implementations). This reduces the dependency between these two classes.

- High-level modules should not import from low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions (e.g., interfaces).

- Abstractions should not depend on details. Details (concrete implementations) should depend on abstractions.

This is valuable because it reduces coupling between two classes, and allows for more effective reuse.

In the example below, the PizzaCutterBot should be able to cut with any tool (class) provided to it that meets the requirements of able-to-cut-pizza. This might include a pizza cutter, knife or any other sharp implement. PizzaCutterBot should be designed to work with the able-to-cut interface, not a specific tool.

Generalized principles

Can we generalize from these? What if we’re not building a pure OO system; are they still applicable?

Enforce separation of concerns

“A module should be responsible to one, and only one, user or stakeholder.“ - Single Responsibility Principle

It follows from the SOLID principles that our software should be written as a set of components, where each one has specific responsibilities. By component, we can mean a single class, or a set of classes that work closely together, or even a function that delivers functionality.

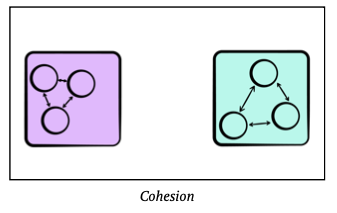

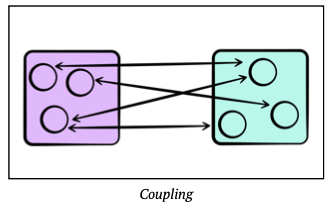

Modularity refers to the logical grouping of source code into these areas of responsibility. Modularity can be implemented through namespaces (C++), packages (Java or Kotlin). When discussing modularity, we often use two related and probably familiar concepts: cohesion, and coupling.

Cohesion is a measure of how related the parts of a module are to one another. A good indication that the classes or other components belong in the same module is that there are few, if any, calls to source code outside the module (and removing anything from the module would necessitate calls to it outside the module).

Coupling refers to the calls that are made between components; they are said to be tightly coupled based on their dependency on one another for their functionality. Loosely coupled means that there is little coupling, or it could be avoided in practice; tight coupling suggests that the components probably belong in the same module, or perhaps even as part of a larger component.

When designing modules, we want high cohesion (where components in a module belong together) and low coupling between modules (meaning fewer dependencies). This increases the flexibility of our software, and makes it easier to achieve desirable characteristics, e.g. scalability.

Diagrams courtesy of Buketa & Balint, [Jetpack Compose by Tutorials](https://www.kodeco.com/books/ jetpack-compose-by-tutorials/v1.0#) (2021).

Interface vs. implementation

“Program to an interface, not an implementation. Depend on abstractions, not on concretions.” - Interface Substitution

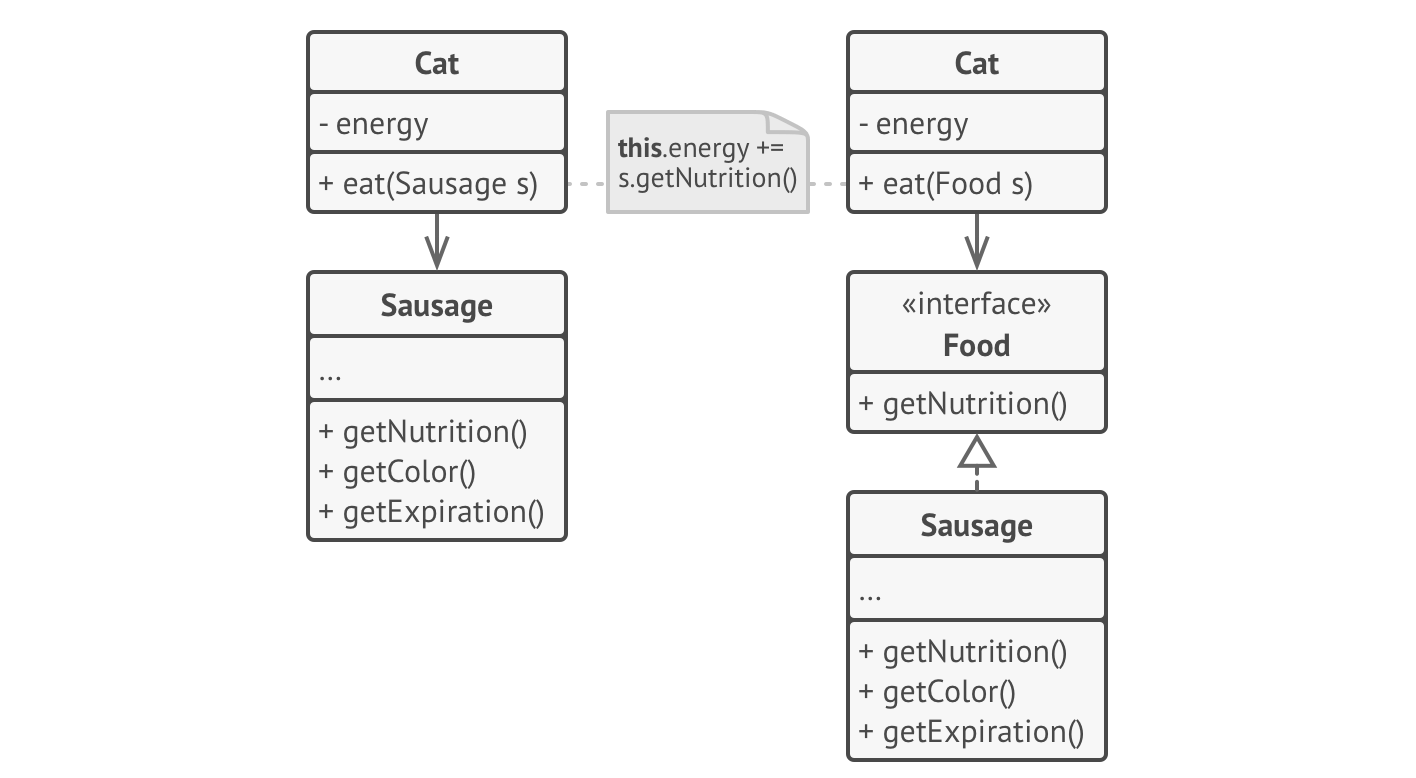

When classes rely on one another, you want to minimize the dependency—we say that you want loose coupling between the classes. This allows for maximum flexibility. To accomplish this, you extract an abstract interface, and use that interface to describe the desired behavior between the classes.

For example, in the diagram below, our cat on the left can eat sausage, but only sausage. The cat on the right can eat anything that provides nutrition, including sausage. The introduction of the food interface complicates the model, but provides much more flexibility to our classes.

Avoid unnecessary inheritance

Multiple inheritance is terrible. Who thought of this? - Prof. Avery

Inheritance is a useful tool for reusing code. In principle, it sounds great: derive from a base class, and you get all of its behavior for free! Unfortunately, it’s rarely that simple. There are sometimes negative side effects of inheritance.

- A subclass cannot reduce the interface of the base class. You have to implement all abstract methods, even if you don’t need them.

- When overriding methods, you need to make sure that your new behavior is compatible with the old behavior. In other words, the derived class needs to act like the base class.

- Inheritance breaks encapsulation because the details of the parent class are potentially exposed to the derived class.

- Subclasses are tightly coupled to superclasses. A change in the superclass can break subclasses.

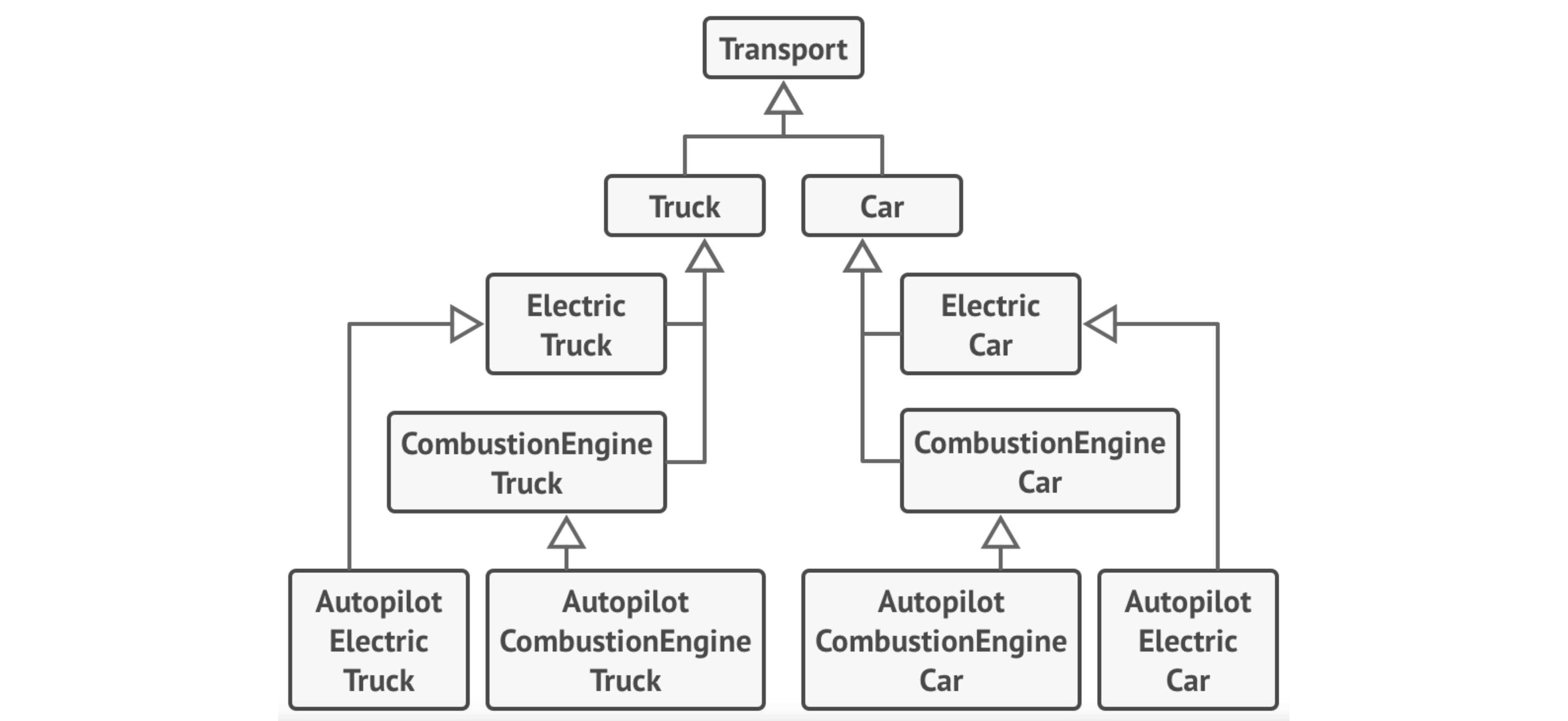

- Reusing code through inheritance can lead to parallel inheritance hierarchies, and an explosion of classes. See below for an example.

A useful alternative to inheritance is composition.

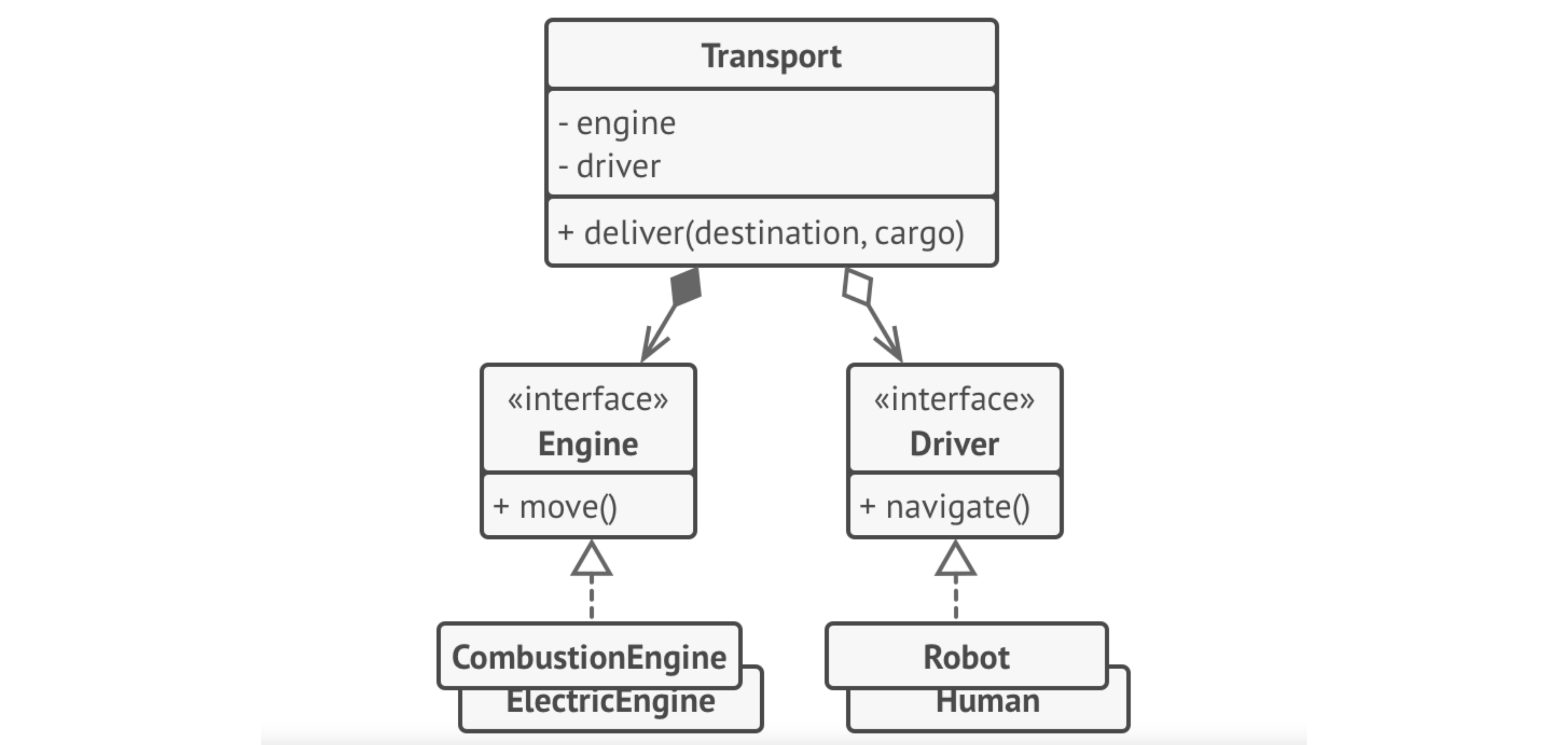

Where inheritance represents an is-a relationship (a car is a vehicle), composition represents a has-a relationship (a car has an engine).

Imagine a catalog application for cars and trucks:

Here’s the same application using composition. We can create unique classes representing each vehicle which just implement the appropriate interfaces, without the intervening abstract classes.

Avoid side effects

At a high-level, functional programming emphasizes a number of principles:

- Functions as first-class citizens

- Pure functions, with no side effects

- Favouring immutable data

Although Kotlin is not a “pure functional language” (however, you care to define that), we can certainly adopt some of these principles.

The easiest, and perhaps the most important to program stability is the idea of avoiding side effects in your code. What is a side effect? It is an unintended change to your program’s state that is not expected when you call a function. In other words, it’s the characteristic of a function that does more than it should.

An obvious example of this is the use of global variables, when are then mutated in a function. As your program grows, you may find more and more functions that update these variables, to the point where it is often challenging to determine what caused them to change! Side effects make your code brittle, more difficult to debug and much more difficult to scale.

The opposite are functions that do just what they are designed to do. A function should:

- Use parameters as its only inputs (i.e. don’t look to any external state when determining a function’s behaviour)

- Mutate that data and return consistent results based solely on the input.

We’ll discuss functional approaches in Kotlin a little later in these notes.

Find the “right” abstractions

Part of the value of an object-oriented approach is that you can model “real-world objects”. We often decompose our context and problem space to identify entities that we wish to model in our software, and build classes reflecting those objects. Then, we can add logical behaviors to our objects to reflect how these objects would react in the real-world.

It’s important to keep in mind a few things when taking this approach:

- Not all software objects need to have corresponding real-world objects (e.g., a software doesn’t need to operate under the same rules as a real factory).

- Conversely, you don’t need to convert every real-world object into a software entity. There is nothing wrong with your models differing from the real-world.

Design patterns

A design pattern is a generalizable solution to a common problem that we’re attempting to address. Design patterns in software development are one case of formalized best practices, specifically around how to structure your code to address specific, recurring design problems in software development.

We include design patterns in a discussion of software development because this is where they tend to be applied: they’re more detailed that architecture styles, but more abstract than source code. Often you will find that when you are working through high-level design, and describing the problem to address, you will recognize a problem as similar to something else that you’ve encountered. A design pattern is a way to formalize that idea of a common, reusable solution, and give you a standard terminology to use when discussing this design with your peers.

Patterns originated with Christopher Alexander, an architect, in 1977 [Alexandar 1977]. Design patterns in software gained popularity with the book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, published in 1994 [Gamma 1994]. There have been many books and articles published since then, and during the early 2000s there was a strong push to expand Design Patterns and promote their use.

Design patterns have seen mixed success. Some criticisms levelled:

- They are not comprehensive and do not reflect all styles of software or all problems encountered.

- They are old-fashioned and do not reflect current software practices.

- They add flexibility, at the cost of increased code complexity.

Broad criticisms are likely unfair. While it’s true that not all patterns are used, many of them are commonly used in professional practice, and new patterns continue to be identified. Design patterns certainly can add complexity to code, but they also encourage designs that can help avoid subtle bugs later on.

In this section, we’ll outline the more common patterns, and indicate where they may be useful. The original set of patterns were subdivided based on the types of problems they addressed.

We’ll examine a number of the patterns below.

The original patterns and categories are taken from Eric Gamma et al. 1994. Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software (link).

Examples and some explanations are from Alexander Shvets. 2019. Dive Into Design Patterns (link).

Creational Patterns

Creational Patterns control the dynamic creation of objects.

| Pattern | Description |

|---|---|

| Abstract Factory | Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes. |

| Builder | Separate the construction of a complex object from its representation, allowing the same construction process to create various representations. |

| Factory Method | Provide an interface for creating objects in a superclass, but allows subclasses to alter the type of objects that will be created. |

| Prototype | Specify the kinds of objects to create using a prototypical instance, and create new objects from the ‘skeleton’ of an existing object, thus boosting performance and keeping memory footprints to a minimum. |

| Singleton | Ensure a class has only one instance, and provide a global point of access to it. |

Builder

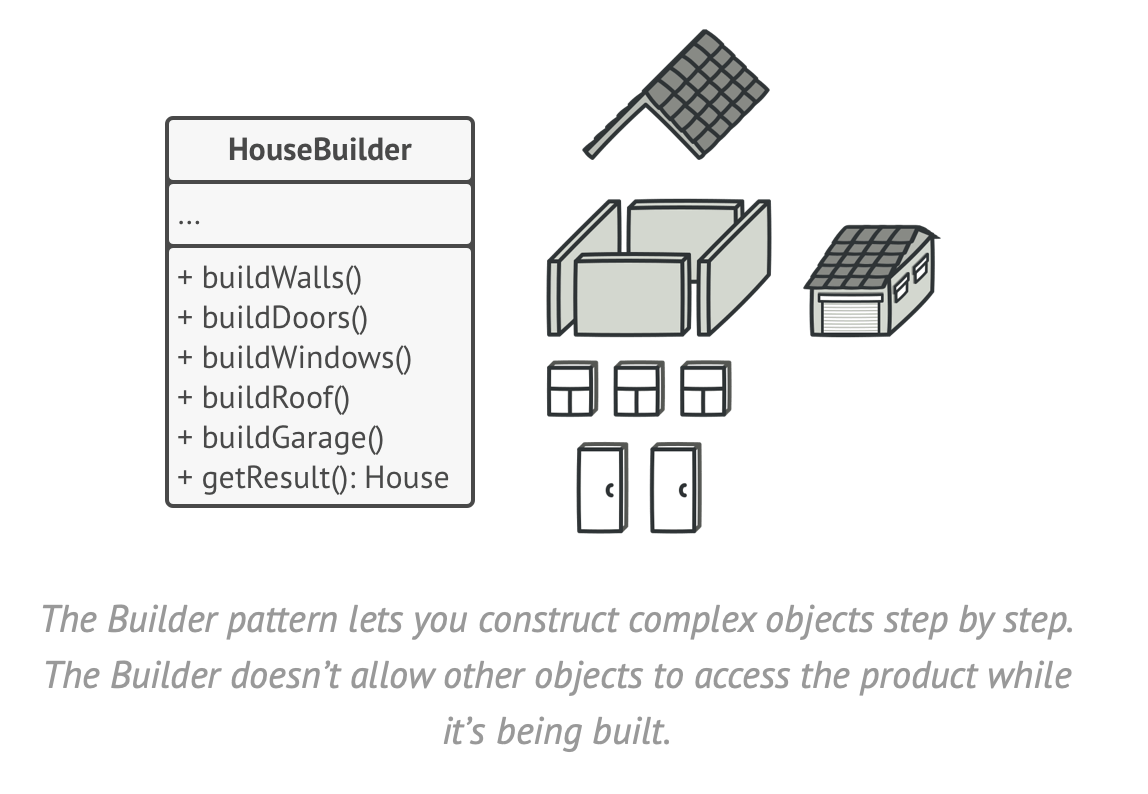

Builder is a creational design pattern that lets you construct complex objects step by step. The pattern allows you to produce different types and representations of an object using the same construction code.

Imagine that you have a class with a large number of variables that need to be specified when it is created. e.g. a house class, where you might have 15-20 different parameters to take into account, like style, floors, rooms, and so on. How would you model this?

You could create a single class to do this, but you would then need a huge constructor to take into account all the different parameters.

- You would then need to either provide a long parameter list, or call other methods to help set it up after it was instantiated (in which case you have construction code scattered around).

- You could create subclasses, but then you have a potentially huge number of subclasses, some of which you may not actually use.

The builder pattern suggests that you put the object construction code into separate objects called builders. The pattern organizes construction into a series of steps. After calling the constructor, you call methods to invoke the steps in the correct order (and the object prevents calls until it is constructed). You only call the steps that you require, which are relevant to what you are building.

Even if you never utilize the Builder pattern directly, it’s used in a lot of complex Kotlin and Android libraries. e.g. the Alert dialogs in Android.

val dialog = AlertDialog.Builder(this)

.setTitle("Title")

.setIcon(R.mipmap.ic_launcher)

.show()

Singleton

Singleton is a creational design pattern that lets you ensure that a class has only one instance, while providing a global access point to this instance.

Why is this pattern useful?

- Ensure that a class has just a single instance. The most common reason for this is to control access to some shared resource—for example, a database or a file.

- Provide a global access point to that instance. Just like a global variable, the Singleton pattern lets you access some object from anywhere in the program. However, it also protects that instance from being overwritten by other code.

All implementations of the Singleton have these two steps in common:

- Make the default constructor private, to prevent other objects from using the new operator with the Singleton class.

- Create a static creation method that acts as a constructor.

In languages like Java, you would express the implementation in this way:

public class Singleton {

private static Singleton instance = null;

private Singleton() {

}

public static Singleton getInstance() {

if (instance == null) {

synchronized (Singleton.class) {

if (instance == null) {

instance = new Singleton();

}

}

}

return instance;

}

}

In Kotlin, it’s significantly easier.

object Singleton{

init {

println("Singleton class invoked.")

}

fun print(){

println("Print method called")

}

}

fun main(args: Array<String>) {

Singleton.print()

// echos "Print method called" to the screen

}

The object keyword in Kotlin creates an instance of a generic class., i.e. it’s instantiated automatically. Like any other class, you can add properties and methods if you wish.

Singletons are useful for times when you want a single, easily accessible instance of a class. e.g. Database object to access your database, Configuration object to store runtime parameters, and so on. You should also consider it instead of extensively using global variables.

Factory Method

The Factory Method is intended to solve the issue of not knowing which subclass to create (i.e. need to defer to runtime, often because of runtime conditions).

The Factory Method defines a way to decide which subclasses to instantiate by defining method whose role is to examine conditions and make that decision for the caller. i.e. instantiation is deferred to a Factory Method.

How to use it?

- Create a class hierarchy for the classes that you need to instantiate, including a base class (or interface) and all subclasses.

- Create a Factory class that instantiates and returns the correct subclass.

Here’s an example of using the Factory Method pattern to read the pieces of a chess board from a data file, and instantiate each object as it’s read.

sealed class Piece(val position: String) // base class

class Pawn(position: String) : Piece(position) // derived classes

class Queen(position: String) : Piece(position)

fun generatePieces(notation: List<String>): List<Piece> { // factory method

return notation.map { piece ->

val pieceType = piece.get(0)

val position = piece.drop(1)

when(pieceType) {

'p' -> Pawn(position)

'q' -> Queen(position)

else -> error("Unknown piece")

}

}

}

val notation = listOf("pa3", “qc5") // method returns list of pieces

val list = generatePieces(notation)

Structural Patterns

Structural Patterns are about organizing classes to form new structures.

| Pattern | Description |

|---|---|

| Adapter, Wrapper | Convert the interface of a class into another interface clients expect. An adapter lets classes work together that could not otherwise because of incompatible interfaces. |

| Bridge | Decouple an abstraction from its implementation allowing the two to vary independently. |

| Composite | Compose objects into tree structures to represent part-whole hierarchies. Composite lets clients treat individual objects and compositions of objects uniformly. |

| Decorator | Attach additional responsibilities to an object dynamically keeping the same interface. Decorators provide a flexible alternative to subclassing for extending functionality. |

| Proxy | Provide a surrogate or placeholder for another object to control access to it. |

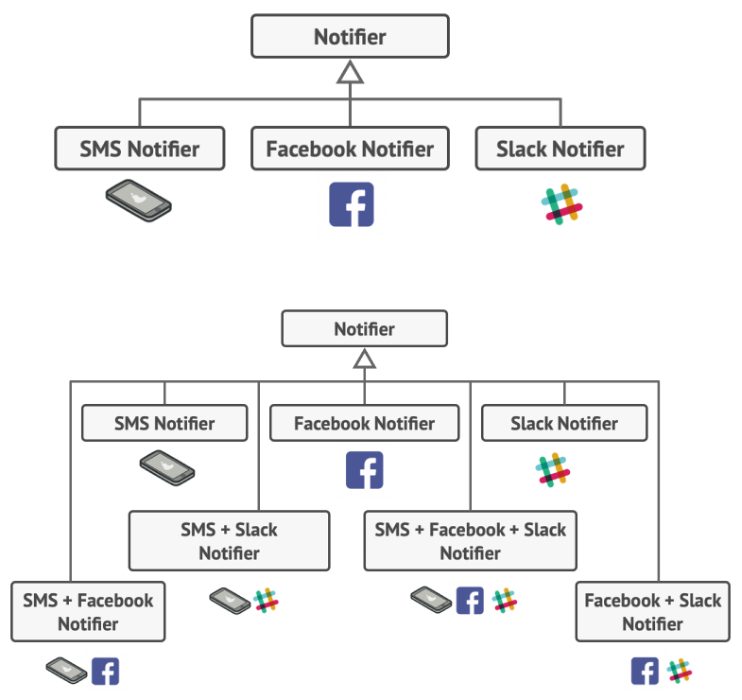

Decorator

The decorator pattern allows you to describe combinations of parameters or classes, without the complexity of having a subclass for each combination.

A decorator allows you to chain together the classes that you want to process a request.

e.g. You are building a message notifier, which allows your application to send out messages.

It’s easy to see how to create a specialized notifier, but what if you want to have a message that is sent to multiple notifiers at the same time? This would be messy as a set of classes, but simpler to compose using a decorator.

Example of a decorator being used.

fun main() {

val logger = Logger()

val cache = Cache()

val request = Request("http://example.com")

val response = processRequest(request, logger, cache)

println("Results: ${response}")

}

// what if I don’t want all of these processors to run?

fun processRequest(request: Request, logger: Logger, cache: Cache): Response {

logger.log(request.toString())

val cached = cache.get(request) ?: run {

val response = Response("You called ${request.endpoint}")

cache.put(request, response)

response

}

return cached

}

fun main() {

val request = Request("http://example.com")

val processor: Processor = LoggingProcessor(Logger, RequestProcessor()))

println("Results: ${processor.process(request)}")

}

interface Processor { fun process(request: Request): Response }

class LoggingProcessor(val logger: Logger, val processor: Processor) : Processor {

override fun process(request: Request): Response {

logger.log(request.toString()) // do appropriate work

return processor.process(request) // pass to next Processor

}

}

class RequestProcessor(): Processor {

override fun process(request: Request): Response {

return Response("You called ${request.endpoint}”) // do appropriate work

}

}

Adapter

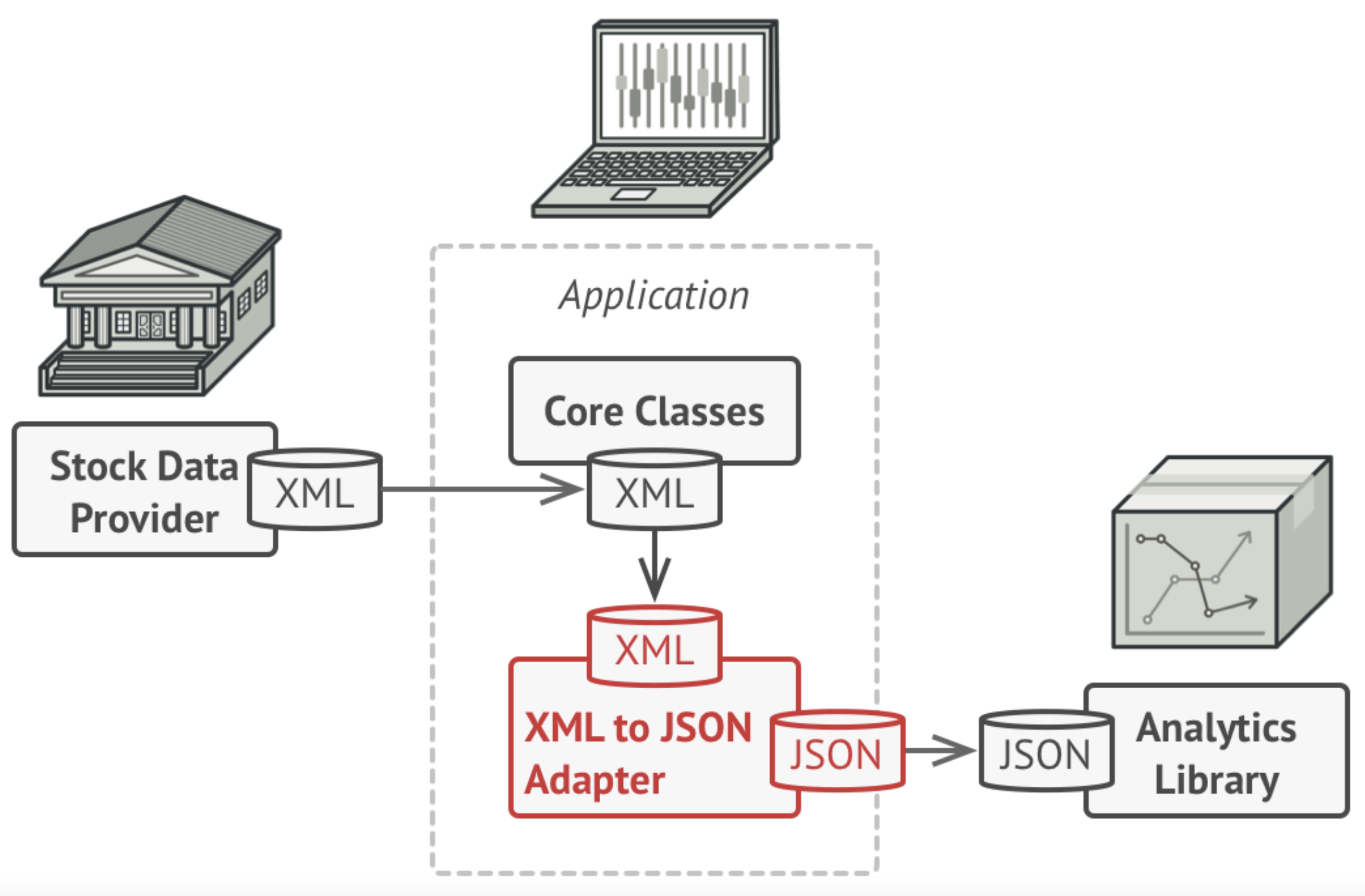

Adapter is a structural design pattern that allows objects with incompatible interfaces to collaborate.

Imagine that you have a data source in XML, but you want to use a charting library that only consumes JSON data. You could try and extend one of those libraries to work with a different type of data, but that’s risky and may not even be possible if it’s a third-party library.

An adapter is an intermediate component that converts from one interface to another. In this case, it could handle the complexities of converting data between formats. Here’s a great example from Shvets (2019):

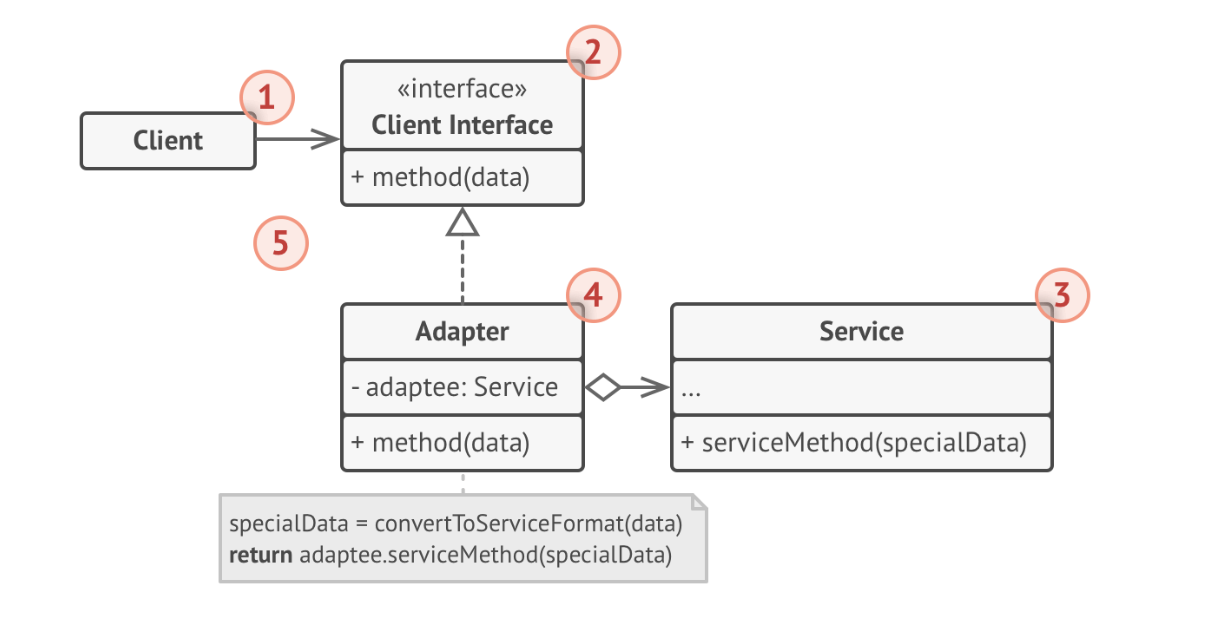

The simplest way to implement this is using object composition: the adapter is a class that exposes an interface to the main application (client). The client makes calls using that interface, and the adapter performs necessary actions through the service (which is often a library, or something whose interface you cannot control).

- The client is the class containing business logic (i.e. an application class that you control).

- The client interface describes the interface that you have designed for your application to communicate with that class.

- The service is some useful library or service (typically which is closed to you), which you want to leverage.

- The adapter is the class that you create to serve as an intermediary between these interfaces.

- The client application isn’t coupled to the adapter because it works through the client interface.

Behavioural Patterns

Behavioural Patterns are about identifying common communication patterns between objects.

| Pattern | Description |

|---|---|

| Command | Encapsulate a request as an object, thereby allowing for the parameterization of clients with different requests, and the queuing or logging of requests. It also allows for the support of undoable operations. |

| Iterator | Provide a way to access the elements of an aggregate object sequentially without exposing its underlying representation. |

| Memento | Without violating encapsulation, capture and externalize an object’s internal state allowing the object to be restored to this state later. |

| Observer | Define a one-to-many dependency between objects where a state change in one object results in all its dependents being notified and updated automatically. |

| Strategy | Define a family of algorithms, encapsulate each one, and make them interchangeable. Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it. |

| Visitor | Represent an operation to be performed on the elements of an object structure. Visitor lets a new operation be defined without changing the classes of the elements on which it operates. |

Command

Command is a behavioural design pattern that turns a request into a stand-alone object that contains all information about the request (a command could also be thought of as an action to perform).

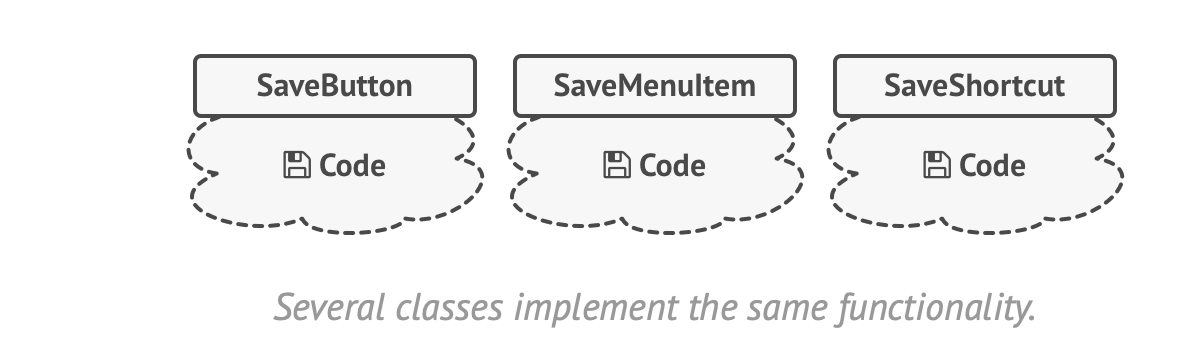

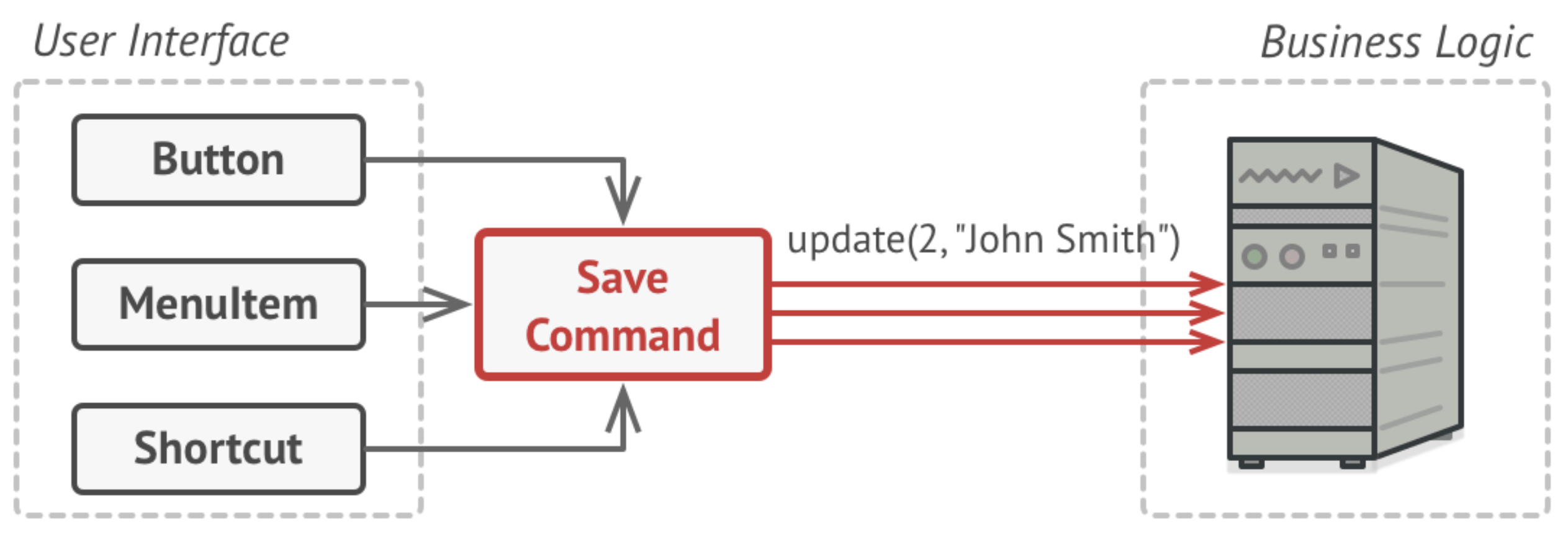

Imagine that you are writing a user interface, and you want to support a common action like Save. You might invoke Save from the menu, or a toolbar, or a button. Where do you put the code that actually handles saving the data?

If you attach it to the object that the user is interacting with, then you risk duplicating the code. e.g.

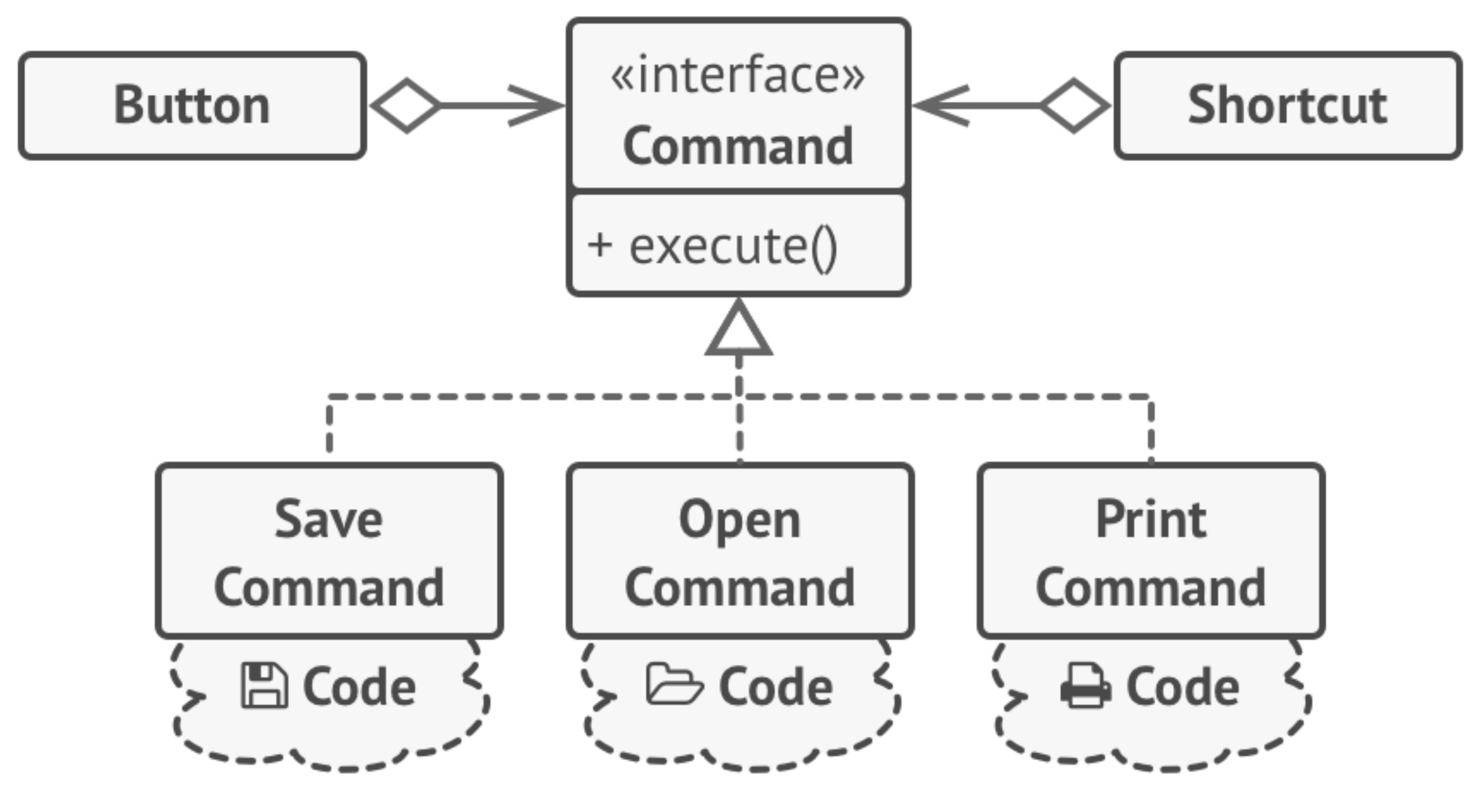

The Command pattern suggests that you encapsulate the details of the command that you want executed into a separate request, which is then sent to the business logic layer of the application to process.

The command class relationship to other classes:

Strategy

The strategy pattern is a way to swap algorithms at runtime. It’s often modelled as a set of interchangeable classes.

Why is this pattern useful? It allows you to add new algorithms or modify existing ones without modifying existing code. It can provides extensibility and flexibility to your solution.

How does it work? Extract algorithms into separate classes called strategies. The original class, called context, must have a field for storing a reference to one of the strategies. The context delegates the work to a linked strategy object.

Here’s an example of some UI fields that we want to extend. We’ll use the strategy pattern to do this.

Here’s a simple example without using this pattern. We have specific specialized classes for each field.

// starting code

interface FormField {

val name: String

val value: String

fun isValid(): Boolean

}

class EmailField(override val value: String) : FormField {

override val name = "email"

override fun isValid(): Boolean {

return value.contains("@") && value.contains(".")

}

}

class UsernameField(override val value: String) : FormField {

override val name = "username"

override fun isValid(): Boolean {

return value.isNotEmpty()

}

}

class PasswordField(override val value: String) : FormField {

override val name = "password"

override fun isValid(): Boolean {

return value.length >= 8

}

}

fun main() {

val emailForm = EmailField("nobody@email.com")

val usernameForm = UsernameField("none"

val passwordForm = PasswordField("*")

}

Let’s refactor this to use the pattern. Our validator interface/classes represent the interchangeable strategies.

// ending code

fun interface Validator {

fun isValid(value: String): Boolean

}

val emailValidator = Validator { it.contains("@") && it.contains(".") }

val usernameValidator = Validator { it.isNotEmpty() }

val passwordValidator = Validator { it.length >= 8 }

class FormField(val name: String, val value: String, private val validator: Validator) {

fun isValid(): Boolean {

return validator.isValid(value)

}

}

fun main() {

val emailForm = FormField("email", "nobody@email.com", emailValidator)

val usernameForm = FormField("username", "empty", usernameValidator)

val passwordForm = FormField("email", "***", passwordValidator)

}

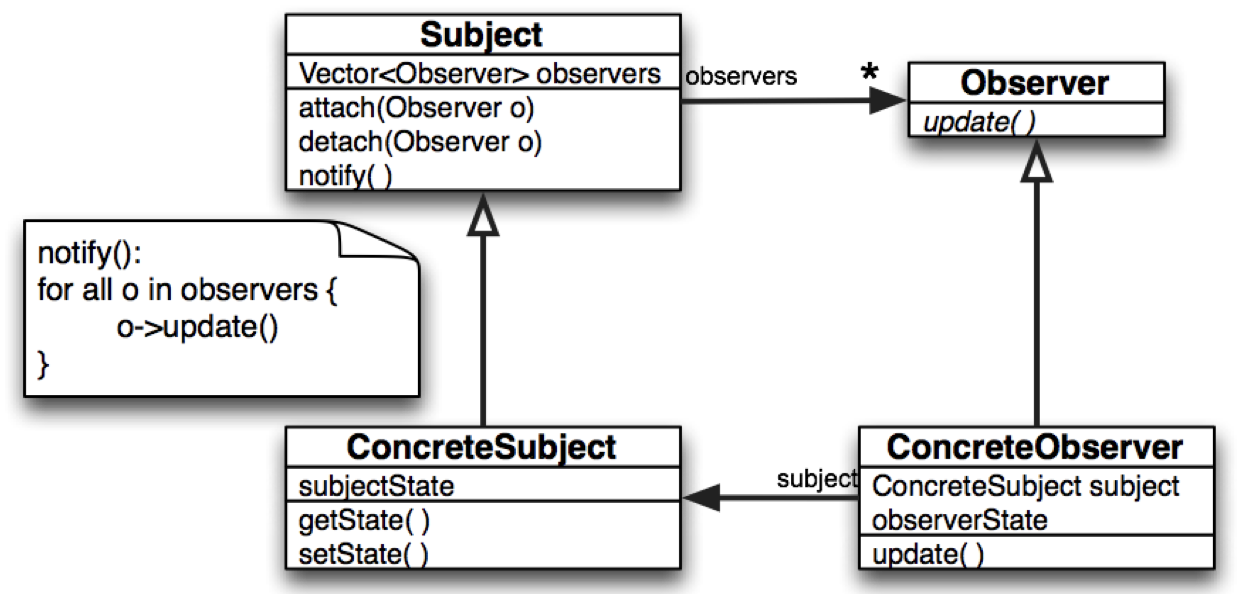

Observer

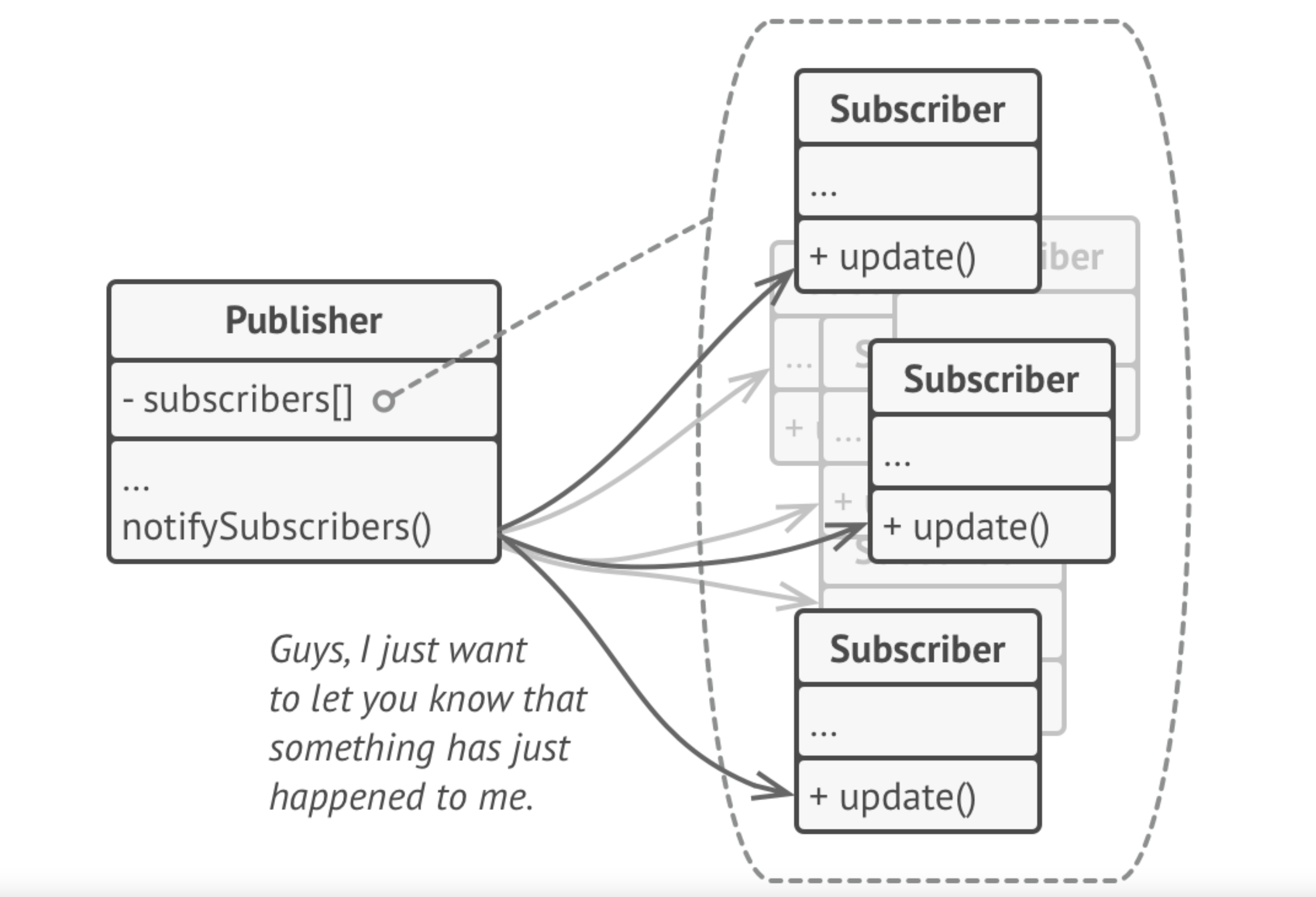

Observer is a behavioural design pattern that lets you define a subscription mechanism to notify multiple objects about any events that happen to the object they’re observing. This is also called publish-subscribe.

The object that has some interesting state is often called subject, but since it’s also going to notify other objects about the changes to its state, we’ll call it publisher. All other objects that want to track changes to the publisher’s state are called subscribers, or observers of the state of the publisher.

Subscribers register their interest in the subject, who adds them to an internal subscriber list. When something interest happens, the publisher notifies the subscribers through a provided interface.

The subscribers can then react to the changes.

A modified version of Observer is the Model-View-Controller (MVC) pattern, which puts a third intermediate layer—the Controller—between the Publisher and Subscriber to handle user input. We’l review this further in User Interfaces.

Last Word